Migrant workers find it difficult to avail the welfare board schemes in Bengaluru as waiting periods are long. Moreover, many labourers are unaware of the healthcare system in Karnataka and often resort to self-treatment.

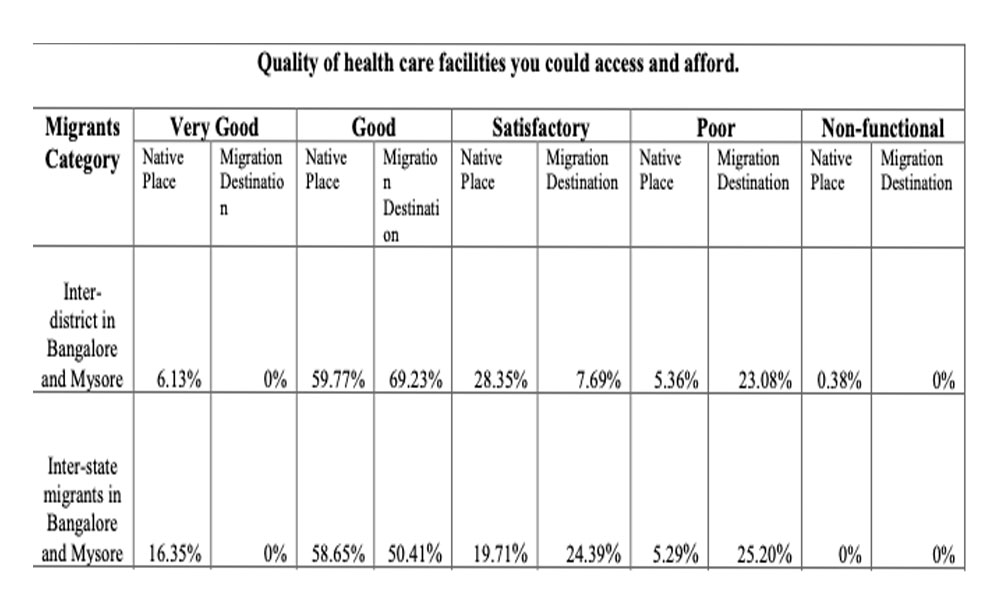

Bengaluru might be a medical tourist spot for the middle and upper class, but for the poor labourers migrating from in and around the state, it is worse than their hometown’s medical facilities, says a Karnataka Evaluation Authority (KEA) report.

Migrant workers must wait one year and 45 days to get any healthcare help from the Karnataka Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Board. Before this waiting period, despite registration, the workers are not eligible. However, the dilemma of migrating to another place for better work during this time frame always looms over them; in which case, they have to restart the process all over again.

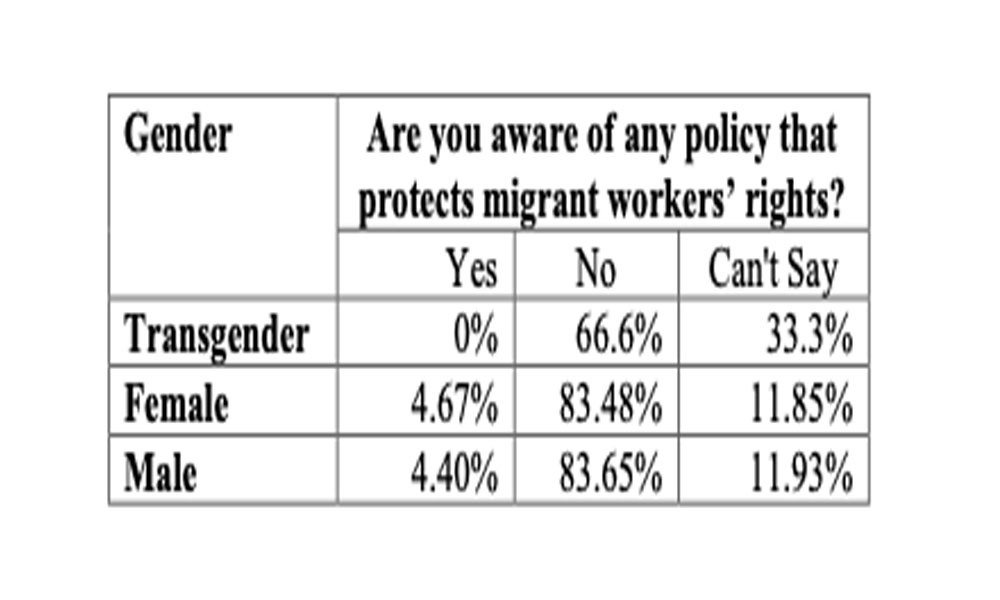

An additional problem for workers from outside the state is that they hardly know about available healthcare help in their destination workplaces.

Amit is 32 years old, from Kolkata, and works at a construction site in Kengeri. The harsh cold in Bengaluru, as compared to Kolkata, is not easy for migrant workers to adjust to as they live in very shabby conditions, said Amit.

“I got very sick when I came here first, around October. My manager suggested me some medicine and I bought it from a nearby pharmacy. Thankfully, the illness subsided. Otherwise, like for a lot of workers I have seen, I would not have known what to do.” Amit said he does not know of the Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) workers or the anganwadi programmes in the area as there has been no awareness camps.

Md. Zaheer Basha, Assistant Labour Commissioner, Karnataka Labour Department, said, “The provisions demarcated in the Inter State Migrant Workmen Act of 1979 are followed. But in terms of awareness camps for about this act, we do not have any such provisions for migrant workers per se.” He added that there are more specific provisions for construction workers, and “because most migrant workers are construction workers, it pans out fine.”

Prameela, with Sampark, a social welfare NGO based in Bengaluru, has worked extensively with migrant workers. “Many NGOs such as ours help out in this regard. We make them aware of their rights, the government schemes, and help them get registered. But the ones who do not come across such help have no option but to bounce around in the private health centres, spending a large chunk of their income.”

She observed that migrant workers, who are not in touch with ASHA workers or anganwadis, spend around 30 to 35 percent of their income on medical treatment in private facilities. “Even for consultations in small clinics, they spend up to Rs. 100 and Rs. 200 each time,” she said.

Prof. Payel Rai Chowdhury, from the department of Human Rights and Human Development, Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata said that healthcare for migrant workers “opens up a Pandora’s box of problems”. However, centralizing healthcare schemes for migrant workers is one of the first steps to solving these problems.

She said, “It is very difficult to look into state accountability because there is no single pocket which can be held responsible. By definition it should be a central government concern because it is across states. But it’s a state issue, and it always will be, even if it is very difficult for the state to work through this without a central system.

Sampark has been negotiating with the Union government to centralize the healthcare schemes under the Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Board. “These boards are there in every state, which is why we have been trying to appeal to the union government to centralise them. This way, repeated registration is not needed whenever a migrant labourer goes to a new state, and the one year waiting period is also not repeated,” Prameela said.

Diseases, accidents and availability

A report by the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) on the quality of migrant workers’ life notes that poor health is a major contributor of Low Quality of Life (QoL) among migrant workers. It further mentions that migrant workers are at higher risk of getting Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) because of lack of easily accessible sexual health services available for them.

Moreover, because of a lack of medical awareness, migrant workers tend to use the healthcare system less compared to the urban population. The workers, therefore, rarely avail existing healthcare facilities provided by the state or their employers.

Prof. Rai Chowdhury said that employers do not provide healthcare for migrant workers because their primary responsibilities are in-state workers. “Because employers know that migrant workers are on a daily wage with temporary contracts, it is easy to neglect their problems,” she said.

She further added that “Migrant workers are more vulnerable to health problems because they are employed in unskilled and semi-skilled labour which carries great risk of occupational hazard. Accidents, toxic gases, smoke, etc. on worksites are common in this occupation.” “They will most likely go to a pharmacy, explain their trouble, and ask for medicine,” said Prameela. She added that availing these schemes is much harder for them because now they have to link their Aadhar card and permanent phone numbers, which many of them don’t have. They also do not have local address proof because their settlements are not permanent. There are many complications.

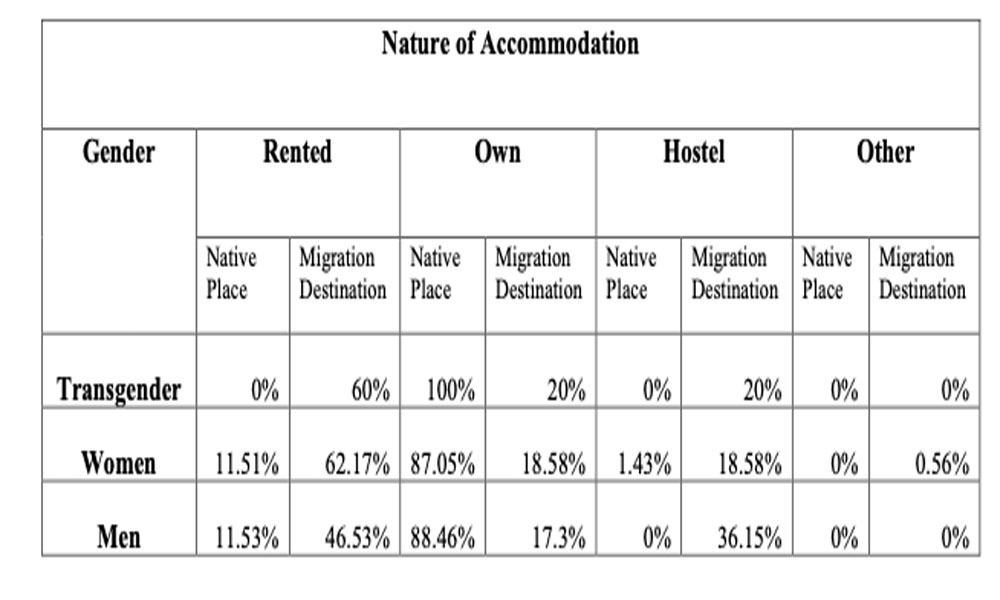

Huts, sheds, and makeshift settlements

The NCBI report noted that 88 percent of migrant workers live in huts, sheds, and other makeshift settlements.

These settlements generally have no running water, electricity, sanitation, or basic hygiene.

“Poor living conditions of migrant workers are crucial for understanding the health problems they go through. This not only would create health problems but also exacerbate existing health problems,” said Prof. Rai Chowdhury.

Accessibility to clean food and water, and proper drainage and sanitation find no priority in their temporary settlements which are often simply plastic tents on worksites. “Because of lack of all the living conditions that we require on a day to day basis, migrant workers become increasingly traumatised and sick as result of their environment,” she added.

“Their 3/5 square meter rooms are cramped with workers, with hardly any space. Sanitation is pathetic and even in cities like Bengaluru, these camps see open defecation,” said Prameela. As a result of unhygienic living conditions and poor sanitation, poor health among migrant workers is a constant problem.

Prof. Rai Chowdhury traced these problems back to the United Nations (UN) conventions on the rights of migrant workers in 1990, and then in 2003. These UN conventions were centered on securing basic human rights for migrant workers and their family members around the world, across geographical borders. However, experts say India’s stand in it since then has been unclear.

“It has been twenty years and there has been a dedicated lack of will on the part of the government to ratify the international law on migrant workers brought up in the 1990 and 2003 UN conventions,” said Prof. Rai Chowdhury. She concluded by saying that the dualistic administrative system of the country has been the top excuse for the union and the state governments to evade responsibility for the migrant workers’ problems, including their healthcare issues.

Pradeep (name changed) also works with Amit and says migrant workers in all states have the same problems. “Here or elsewhere, we hardly get decent living quarters or medical help. So many of us in one room will always be a problem, because if one of us gets sick, all of us eventually end up getting sick.”

Great report. I had heard a few similar cases and the report validates the issue.