Unawareness and negligence stalls the progress of pilot micro irrigation project set up in Hungund taluk.

Hungund taluk of Bagalkot district faces age-old issues among the farmers and the government. Farmers are accusing the government of negligence, the involved company saying that they haven’t received any money for the last two years and the government engineers stating the problem lies in the unwillingness of farmers to understand the project.

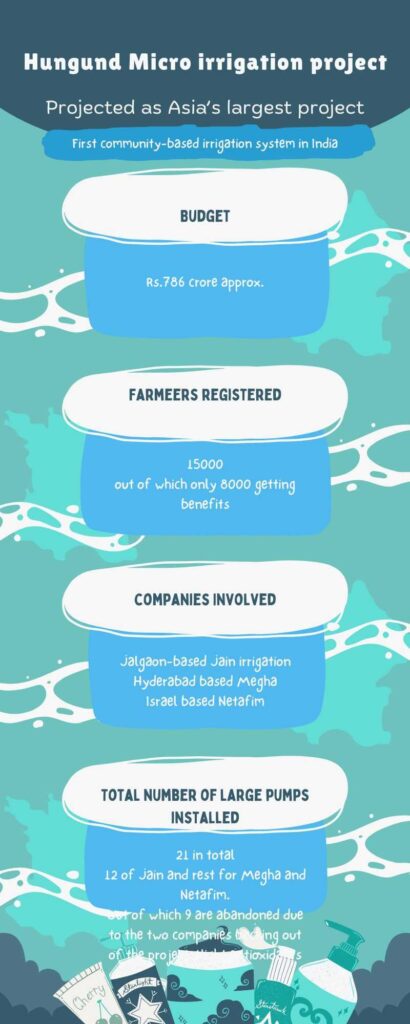

This is the scene of the massive Rs. 786 crore micro irrigation pilot project set up in Hungund, showcased as Asia’s biggest community-based irrigation project. All involved parties are accusing each for the failure of the project.

This is costing the farmers of the area who were supposed to get help with the microirrigation system.

Bagalkot district of Karnataka is facing one of the worst droughts in the last few decades. The massive community-based micro-irrigation system installed in the taluk is unable to ease the situation. Usually, crops are harvested twice in the Kharif and twice in the Rabi seasons. This year, farmers were only able to harvest one crop in the Kahrif season, and no seeds were sown for the Rabi season, due to water scarcity. The year 2023–24 is also declared drought-stricken for the Bagalkot district and the surrounding districts.

Bano Begum and Mahmud Bari own a piece of land near the Ramthal pump house in Hungund taluk. They have been farming on the land for three generations. Bano Begum says that they have had no water for farming for the last 5–6 months; therefore, they did not sow seeds in the Rabi season and the Kharif season, and they have only cultivated one crop since last year. “Farmers in this area have a water issue every year, but this year the problem has intensified. This is the first time we have not sown seeds for any crop in Rabi season, in the last few decades.” She added.

Mahmud Bari said that there was a big water pipeline installed on the side of his farm, under the micro irrigation project. “The big pipeline was supposed to divide into smaller pipelines, which went into my farm and the surrounding farms. After a month or two, the pipeline busted, and the water came into my farm and destroyed the crops. There was no compensation paid by the company or the government.”

The project was started in the years 2014–15 and installation of the main pump was completed around 2017. It was said that around 15,000 farmers were registered to benefit from the project. However, after a decade of initiation, the project has not reached its intended goal. According to officials only 8,000 of the registered farmers have drip irrigation systems installed in their farms.

The project comes under Krishna Bhagya Jal Nigam Limited (KBJNL), and the Karnataka government appoints officers to take care of the installation, maintenance, and inspection of the project.

T.V. Govindraj, assistant engineer under KBJNL, who is posted as the head officer to look after the drip irrigation system in Hungund Taluk, said that till now, only around 8,000 farmers have micro irrigation systems installed in their farms.

He added, “Since it was voluntary for the farmers to opt for drip irrigation, many have chosen not to. Even those who have drip irrigation installed on their farms take out water directly from the main storage pumps. They go for flood irrigation instead of micro-irrigation. Therefore, all the installation and planning go to waste. They are not interested in lateral micro irrigation; they prefer flood irrigation.”

M.V. Agadi, who is a site engineer at KBJNL and does regular inspections on the farms, said, “The farmers are not cooperating with us; they become anxious and break the walls or main pipes to take out water directly. Due to this, the water does not reach all the farms proportionally; already, we have water scarcity, and this adds to the problem.”

He added that the government, with the help of Dharwad WALMI (the water and land management institute), arranged many awareness programs to educate and include the farmers in the project, but in the end, not much changed. “I was manhandled by some farmers after I questioned them about breaking the walls of the tank. It is not under our power or jurisdiction to act against the farmers. We have complained to the police many times but no action is taken due to pressure from several local political groups.” he said.

According to a report by the central water board on Hungund Taluk, the area has been drought-stricken for many decades.

To ease the problems of farmers due to the constant drought situation in the taluk, the government of Karnataka brought in a Rs. 786 crore micro-irrigation, which covers 24,000 ha of land. The micro-irrigation project included both drip and drop irrigation systems.

The implementation project was divided between three private firms. The total area was divided into two parts. 11,700 hectares of land were given to a joint venture between the Israel-based company Netafim India Private Ltd. and Hyderabad-based Megha Engineering and Infrastructure Limited (MEIL). The other 12,300 hectares were given to the Jalgaon-based Jain Irrigation firm.

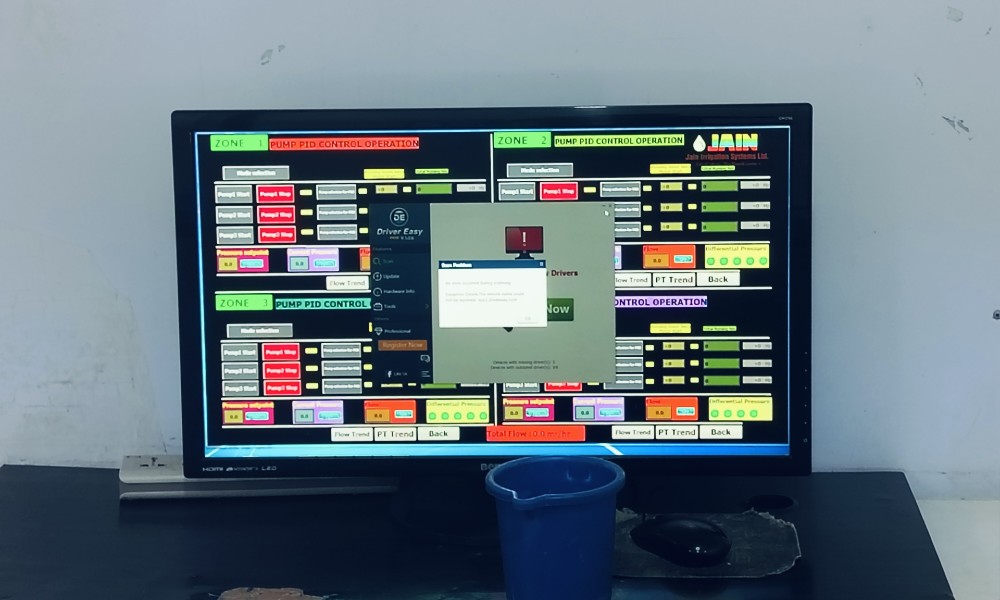

The project was supposed to bring water from the backwaters of Krishna River through the Allamati project. In addition, the project also draws water from Ghataprabha and Mallaprabha rivers nearby to irrigate the fields. The system operates through wireless automation, and a separate power line has been provided for the pumphouse.

While the system was brought in to help farmers and divide water evenly among a drought-stricken area, the situation of the project, including the firms involved in the project, has not been very good. In addition, it has not been much help to the farmers in the area.

The involved firms have also hit a rough patch over the years with the government. Two of the three firms backed out of the project last year. Megha and Netafim have taken their jurisdiction and involvement out of the project and even closed their regional offices. Ravi, who used to work in the regional office of Netafim, said that Megha and Netafim have taken their hands off the project and transferred all of it to the government.

T.V. Govindraj agreed that the two firms have removed themselves from the project, but they have yet to receive all the documentation regarding the transfer. As for now the installed systems which came under Netafim and Megha are not operational.

Naveen is one of the two pump operators who are handling the Ramthal pump house, which is the center of the project. It is the place where all the water coming from the lift irrigation system near the Alamatti dam built on the Krishna River comes and then is redirected towards farms. He said, “The two firms left the project in October 2023, and since then, the pumps operated by them have been left unused. From December on, there is no water coming at all.”

There are a total of 21 pumps in the main pump house, of which 12 are operated by Jain Irrigation and nine are handled by Megha and Netafim.

Naveen also added that previously there were six pump operators, but after October, four of them were transferred, and now only two are left.

The Megha firm has set up many lift irrigation, river linking, and drip irrigation projects across India. Its business is spread across Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, etc.

Jain Irrigation Limited, the other firm involved in the project, has its complaints. Praveen Mallapur, the project in charge of the Jain irrigation, said, “For the last two years, there has been no payment made for the operation and maintenance costs by the government. We have not even fully received our bank guarantee (BG) amount. We are somehow managing to still operate at our costs.”

From December 4th, 2023, no water is released from the Alamatti dam due to less rainfall; therefore, the taluk is facing a severe water crisis. Even before December, of the year 2023, a very small amount of water was released.

Srisail, the agricultural officer of the area, said that last year, due to less rainfall, there was very little water released in the Kharif season. Due to this, the farmers could not only harvest one crop; they usually went with two crops.

He said “The soil here is generally black, which absorbs too much water. We advise farmers not to go with very water-intensive crops like rice but rather choose crops like chilly or millets. But the change is happening at a very slow rate; only five percent of the farmers have shifted to less water-intensive crops.”

Basavaraj is another farmer in Hungund Taluk who owns farmland near the Ramthal pump house. He said, “I have a micro irrigation system installed in half of my total farmland, but it has not helped me so far. Proper amounts of water are not released during cropping seasons; they are rather inconsistent throughout the year. This year and last year, there was almost no water released; therefore, I only had one crop in the whole year. Usually, farmers in the taluk go for one or two crops in each cropping season combined.”

He added that nobody from the government or any private firm has come yet in the last year to inspect or hear their problems.

He urges that a stronger check on the quality and implementation of the project and better regulation of water during cropping seasons would help solve the issue.

Dr. M.N. Thinmmegowda a professor at the University of Agricultural Sciences, Bangalore, whose expertise is in Rainwater harvesting and micro-irrigation said that there is a problem from all three sides and needs to be dealt with in a better way.

He said “The project is one of a kind as it is a country’s first community-based drip irrigation system. If it becomes successful it will open doors for many such projects in different parts of the country. This type of project is like a boon for drought-stricken areas, as almost two or three times the land can be cultivated using the same amount of water. If it would have been implemented properly, it would have solved the problem of farmers in the area to a large extent.”

He added that in projects like this, the farmer whose land is at the beginning and whose land is at the last would get an even amount of water. Which would not be possible in Flood irrigation or any older irrigation system. There is also no water logging or increase in the salinity of the soil. The system is environment-friendly as it does not deplete the nitrogen and oxygen content in the soil.

He said that organizations like Karnataka State Farmers’ Association (KRRS) and other local farmer’s associations do not have a very strong presence in the area. “It is easier to negotiate and deal with farming associations than to deal with farmers directly one by one. In this case, since the number of officials in the local KBJNL office is very low, their coordination with the local panchayat and farmers may not be good. As a result, there is a disconnection between the state government and farmers.”

He added that a separate body consisting of members from local farming associations, private company representatives, and government engineers may solve the issues associated with the project.

He said “At any cost, the private companies involved should not be allowed to leave the project midway. The government officials are not trained to handle such projects and it will muck things up even more.”

M.V. Agadi said, “Every year, officials from different state governments like Maharashtra, Odissa, etc. come on a visit to see the drip irrigation project. It has been projected as Asia’s biggest community-based drip irrigation project. But the reality is far from it.”