Experts say that people often prefer sterilization as a form of birth control due to its permanence and convenience, and a lack of awareness regarding other temporary methods.

Amidst the scorching heat outside the Lingasugur Taluk Government Hospital, a group of women were huddled together in whatever shade they could find near the hospital. While the women rocked their babies to sleep in makeshift hammocks crafted from colourful sarees, Ravi, a resident of Hanumangudda, stood near the hospital wall alongside other men who had accompanied their wives to the hospital.

Ravi, who already has a daughter and a son, shared that he faced mounting family pressure to not have any more children and that was why he had decided to have his wife undergo a tubectomy. However, when a vasectomy was suggested as an alternative, Ravi’s reaction was one of astonishment. “Is there an operation for men too? Is that even possible?” he asked repeatedly out of disbelief. Despite explanations regarding its safety compared to tubectomy, he remained sceptical, adamantly refusing to consider the option for himself. This encounter underscores the deeply ingrained gender dynamics influencing reproductive health decisions, not only within the confines of Lingasugur or Ravi’s story but echoing a broader societal narrative.

There is a huge disparity in the sterilization rate between men and women in the Lingasugur taluk of Karnataka. Pranesh Joshi, the Block Health Education Officer of Lingasugur, said that while around 250 to 300 tubectomies are conducted in the Taluk Government hospital every month, only one no scalpel vasectomy was conducted there in the last three years. He said that this was despite the awareness programmes conducted by the hospital about temporary methods of birth control.

Sharadha Rathore, an ASHA worker based in Lingasugur, shed light on the challenges of counselling rural communities regarding birth control, especially when compared to their urban counterparts. “Educated individuals usually understand that our guidance is for their own well-being, however, this is not always the case with less educated populations,” she said. Many individuals from rural areas express a preference for larger families, often driven by a desire for male offspring, which can hinder their acceptance of birth control methods, she said.

She further elaborated on the difficulties they encounter when suggesting vasectomy as an alternative to tubectomy and emphasising its safety. “Residents often react negatively, asking us to focus solely on our duties and refrain from lecturing them,” she said. Despite facing criticism, she said that they have grown accustomed to such reactions, considering them as a part of their work and moving on.

However, these trends are not isolated to Lingasugur. According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS 5) data, the female sterilization rate in Karnataka surged to 57.4 percent from 48.6 percent in the previous NFHS 4 report. Conversely, male sterilization in the state plummeted to zero percent from 0.1 percent in the same period. Data reveals that 69 percent of currently married women and 65 percent of married men aged 15 to 49 in Karnataka are either sterilized themselves or have a sterilized spouse. Additionally, 45 percent of men in the same age group feel that contraception is solely a woman’s responsibility and that they should not have to worry about it.

Comparatively, Karnataka’s female sterilization rate far exceeds the national average. NFHS 5 indicates that India’s female sterilization rate has increased to 37.9 percent from 36 percent in the previous NFHS 4 report, while male sterilization remained stagnant at 0.3 percent over the same period.

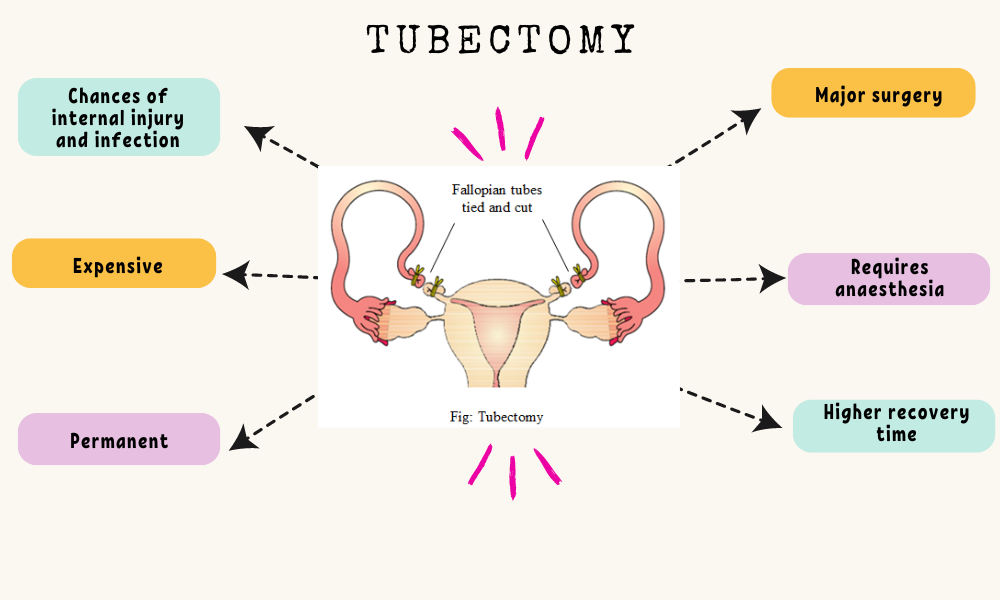

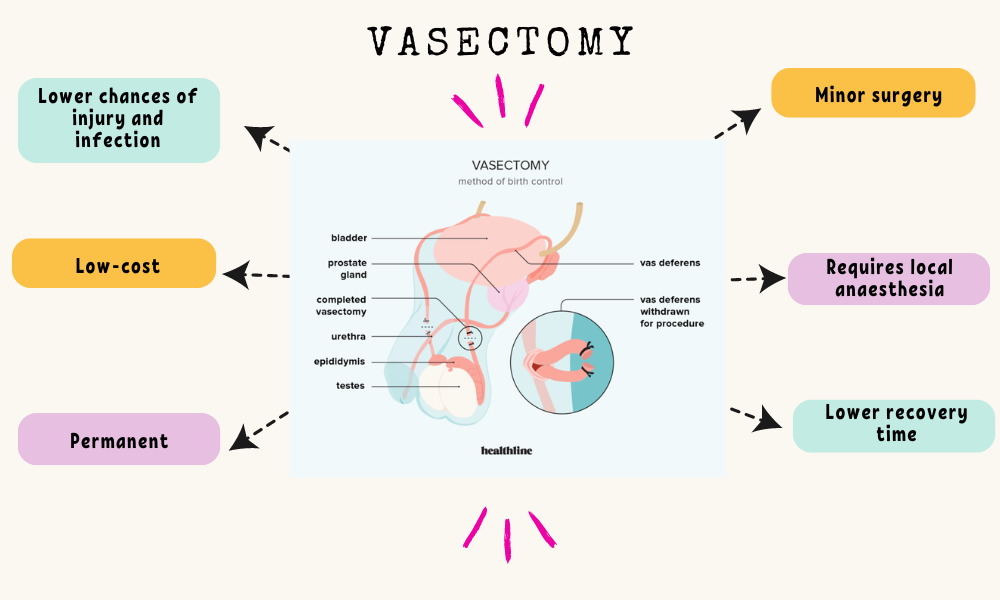

Dr. Shubha Rama Rao, President of the Bangalore Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, highlighted the advantages of vasectomy over tubectomy as a contraceptive measure, citing its minimally invasive nature. “Vasectomy, often referred to as a ‘lunchtime surgery,’ can be swiftly conducted under local anaesthesia, unlike tubectomy, which requires a minor surgery and general anaesthesia,” she explained. Notably, vasectomy requires a shorter recovery period and is more cost-effective compared to tubectomy, she said.

She said that the prevailing myths and misconceptions surrounding vasectomy lead to its lower adoption rate. “Men often fear that vasectomy would negatively impact their virility or ejaculation, despite these concerns being untrue,” she said. Additionally, while some women opt for tubectomy after delivery or voluntary abortion for the sake of convenience, she stressed that this was not the sole reason behind their choice. “Some women still adhere to traditional gender roles, viewing men as primary breadwinners. Hence, they resist vasectomy for fear of compromising their husbands’ health and ability to provide for the family,” she added.

Moreover, she pointed out that women preferred sterilization over other temporary methods of birth control such as contraceptive pills due to their apprehensions about its effectiveness and the simplicity and reliability of surgical sterilization.

Nevertheless, doctors continue to promote awareness about long-acting reversible contraceptives, offering viable alternatives to sterilization until individuals are certain of their decision, she said. “We discourage young women with one or two children from undergoing tubectomy, keeping in mind the various socio-economic factors in today’s society,” she said. While offering counselling on birth control, doctors must tailor their approach to each patient’s unique circumstances rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all approach, she concluded.

Experts say that vasectomy is a better birth control measure when compared to tubectomy, due to its non-invasive nature, lower recovery time, and reduced cost.

Shardha, a 22-year-old, from Devanakonda, was at the Lingasugur Taluk Government Hospital to undergo a tubectomy. She was accompanied by her sister and mother and had to leave her children Shravani and Sharath back at home. Both her sister and mother too had undergone sterilization previously. Basamma, her sister, said, “Since she has two children now, she decided to undergo sterilization. In our village, it’s mostly the women who bear the burden of contraception. Men say that they are too busy with their work to consider such matters. Even if we suggest our husbands get the sterilization done, they would decline it and force us to get one. They say that the operation might hurt them, so we should get it done instead.” She added that the fear of infidelity was another factor that prompted their husbands to force them to undergo tubectomy. “Some men distrust their wives so much that they even question the paternity of their children. So, they force their wives to undergo sterilization, believing that this would prevent them from being cheating on,” she said.

Rose Mary, the Family Planning Counsellor at the Taluk Government Hospital said that they follow the cafeteria approach when they counsel people on birth control. “We offer them alternatives, both temporary and permanent, and leave the decision up to them. If we force them to prefer one over the other, they might think that we have a certain agenda that we are trying to push, hence we refrain from it,” she said.

She said that people prefer permanent sterilization over temporary methods due to a lack of knowledge and the ease and permanence offered by sterilization. “Couples feel that their responsibility is over once they have a couple of children, and that they must undergo sterilization to avoid future hassles such as unwanted pregnancies. However, they are wary of relying on temporary methods of birth control fearing that they might fail,” she said. She added that the difficulty in continuing the dosage of contraceptive pills such as Mala N and the hassle of regularly visiting the hospital to get a shot of contraceptive injections such as Antara were other factors that discouraged them from opting for temporary methods of birth control. She added that there was a prevalent disinterest among the people to follow the birth control measures administered by the officials.

She pointed out that even if men were willing to undergo vasectomy, it was usually the women who were against it. “They fear that the surgery might adversely affect the health of their husbands, usually the sole earning member of their family, and hence take it upon themselves to undergo the surgery,” she said.

She added that undergoing tubectomy was the only way for some women to avoid marital abuse. “During the counselling sessions, many women complain that they are forced by their husbands to have sex with them every night and have more children. But when they refrain from it, they are threatened with consequences including divorce,” she said. For such women, permanent sterilization is the only way for them to avoid future pregnancies without being caught by their husbands while using temporary methods such as contraceptive pills. “Mostly these women undergo sterilization when they visit their parents’ homes without their husbands’ knowledge,” she said.

In her decade-long career at the hospital, she had also observed a few cases of couples who regretted undergoing sterilization. “These women underwent the surgeries when they had young children. Death of their children or remarriage shattered their plans, leaving them with no way to have another child,” she said.

Despite the diversity in their appearances and clothing, the women gathered in the meagre shade near the hospital waiting for their turn to get sterilized shared a striking commonality: their stories that echoed a lack of agency. They each unveiled narratives written in powerlessness. Their tales exposed continuing preferences for sons over daughters and underscored the prevalence of myths shrouding India’s most favoured method of birth control.

Dr. Savitha B.C., a professor at the Department of Sociology at Bengaluru City University, said that Indian society has undergone significant changes in the last 30 years, with a considerable shift from joint families to nuclear families. “Couples today are less interested in having children immediately after marriage or in having kids at all. This change is more visible in urban regions, making family planning and birth control more commonplace,” she said.

However, she pointed out the persisting gender gap in family planning. Birth control is primarily seen as a woman’s responsibility, and as a result, women are the ones who undergo sterilization more often. “Vasectomy rates are much lower in India, as the society is still patriarchal at its core and does not accept men playing an active role in family planning,” she said. “Every act of a woman is still scrutinized by men and controlled by everyone but her. This extends to decisions about birth control and other choices that can impact her health,” she said.

She opined that young couples’ overreliance on sterilization as a birth control method is because they perceive children as a burden that demands responsibility and attention, which goes against their choice of lifestyle and freedom. She remarked that this in the long run could threaten one of Indian society’s strongest features – its family structure.

Studies have found that female sterilization rates are higher in women belonging to poor communities and those deprived of education. They pointed out that a lack of autonomy and awareness among women, the husband’s decision-making power on fertility, and fear that vasectomy would affect one’s masculinity and sexuality were other reasons that influenced this disparity.

In the year 1975, India was forced into Emergency under the leadership of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. The following months have since been marked as one of the darkest periods in the annals of Indian democracy by historians. Yet, amidst press censorship and governmental overreach into democratic institutions, this era is particularly remembered for the enforcement of a scheme spearheaded by Sanjay Gandhi, the Prime Minister’s younger son.

In 1976, the second year of the Emergency, the country witnessed the imposition of forced mass sterilizations in a bid to curb the rapidly growing population. Authorities resorted to coercive tactics, rounding up individuals and herding them onto buses bound for sterilization camps. Many men underwent the procedure without adequate information or consent, while civil servants faced dire threats of job loss if they exceeded a specified number of children.

In the aftermath of this political turmoil, a new government emerged, bringing a shift from coercive measures to a more inclusive approach to family planning. Under this revised program, couples were empowered to make informed choices regarding contraception, with options ranging from female and male sterilization to intrauterine devices, oral contraceptives, and condoms.

Even decades after the forced sterilization programme, India continues to grapple with the dominance of female sterilization as the primary method of birth control. However, the wielder of coercion is no longer the government, but society and lack of awareness.

In the 1970s, the birth control programme was viewed as a necessity amidst India’s rapid population growth. However, the overreliance on sterilization presents a looming threat today. The replacement fertility rate for India has dropped to 2, with wide variations within the country. This is below the required 2.1 children per woman to maintain population stability. Economists feel that this drop in the total fertility rate might adversely impact the economy, leaving the country with a mostly older population soon, highlighting the urgent need for a diversified approach to family planning in the face of evolving demographic challenges.

As long as individuals like Ravi choose not to actively engage in family planning, and women like Shardha are made to believe that birth control is solely their responsibility, ignorance, oppression, and lack of autonomy will persist, perpetuating age-old injustices, including in the form of gender disparity in family planning.