Karnataka ranks among top states in rehabilitating street children through the Child Protection Services Scheme.

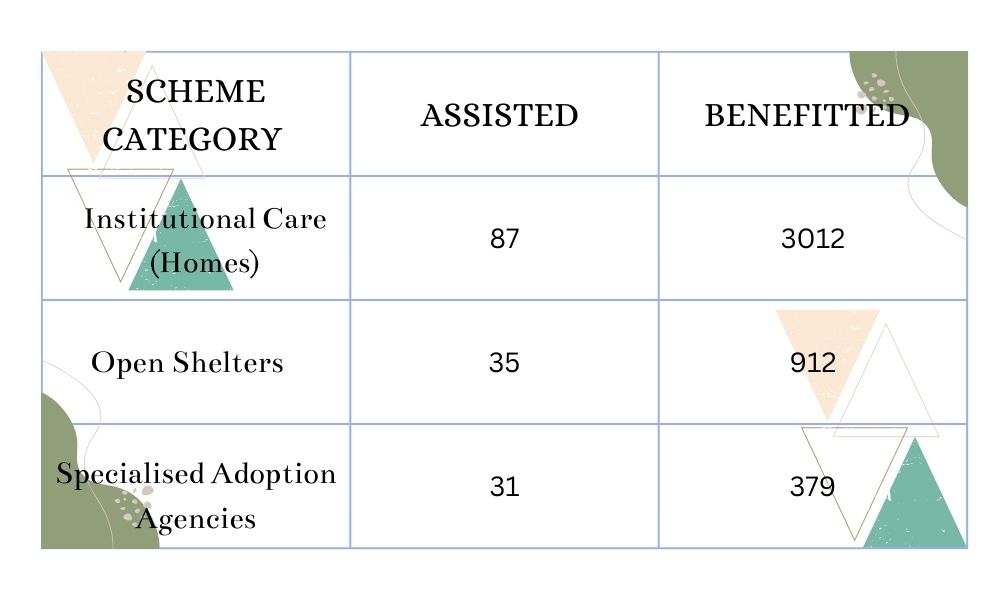

A 2021 government of India report shows that Karnataka ranks among the top ten in the list of states where street children have been helped through the Child Protection Services Scheme, also known as the Integrated Child Protection Scheme (ICPS). In total, the scheme has benefitted 4303 children, while 153 children have been assisted. In all three broad categories of the scheme—institutional care homes, open shelters, and specialised adoption agencies—Karnataka ranks among the top ten states. However, problems like lack of sufficient child-centric legislation, socio-economic issues, and migration for work continue to hinder significant development.

The report notes that under the Institutional Care Homes category, Karnataka ranks seventh where 3012 children were benefitted (rehabilitated), while 87 were assisted (partially or temporarily helped). Karnataka ranks second highest in open shelter (where kids can take shelter temporarily) development as through the open shelters, 912 children benefited and 35 were assisted. Karnataka also ranks second in rehabilitating children through specialised adoption agencies—379 children were benefitted and 31 were assisted. Despite the comparatively better performance, experts say the scheme continues to face several challenges as Karnataka, in 2022, ranks third highest in the number of street children.

An official from the Directorate of Child Protection said that, the ICPS has made a difference, despite the growing numbers. “We have open shelters, child care institutions, and adoption facilities that we use to rehabilitate them,” she said. However, she noted that the larger struggle in rehabilitating street children is that parents take the children home. “We have a lot of children who run away from home because of abuse or neglect. Children often runaway because they are coerced by their parents to work, which they do not want to. But our procedures require us to look for the parents before we can institute the child in our system,” said the official. During this phase in the procedure, the parents take back the children and they return to being on the streets during the day and returning home at night said the official. “Once a child is taken into the system, we give them formal education, medical tests, and even counseling,” she concluded.

Nagamani, member of the Bengaluru-based children’s NGO Child Support Foundation, said that the Scheme would work better in coordination with legislations such as the Right to Education Act, and Child Labour Prohibition Act. “The scheme can be much more effective if different government bodies could work together on different legislations. For example, when children runaway and don’t show up to school, school administration should follow up on the child and inform the authorities concerned.” She further said that stringent actions against employers of street children by the departments under Child Labour Prohibition Act would also help in monitoring the children and their number. “But the problem is that street children do not have established employers. So, when a first information report (FIR) is filed, it is important that an employer is traced, or else the case cannot be taken forward by the government authority and is dropped. The child goes back to the street,” said Nagamani.

Prof Payel Rai Chowdhury, head of Human Rights and Human Development of the Rabindra Bharati University, mentioned that India lacks enough legislation in terms of children’s protection, specifically. “The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection) Act is the only child-centric act. There are mentions of children in other acts such as the Hawkers Act, but there aren’t many other acts for children, per se. This limits the legal growth for children, especially street children for whom the government bodies are the only protection,” said Professor Chowdhury. She said that despite this, the Supreme Court has played a very active role in paving the way for child rights through several public interest litigation (PIL) cases.

Prof Chowdhury said that diverse distribution of street children occupation, also poses a problem in rehabilitating them. “Since they don’t have a permanent shelter, the children also don’t have permanent occupations. Some a rag-picker one day and newspaper seller the other,” said Professor Chowdhury. She added that this makes them easy targets for commercial use through physical and sexual exploitation. “They are the most vulnerable minority owing to them being minors; this gives them the most right to jurisdictional protection.”

Both, the Directorate of Child Protection and Nagamani, mentioned that the inflow of migrant workers into the state has also greatly contributed to this problem. “Migrant workers move every few months and their children cannot avail proper education. This leaves them with little choice but to go on their own to live in the streets and earn whatever they can picking rags and trash,” said Nagamani.

A 2012 United Nations report terms street children as children who depend on the streets for their survival or development. The report further says, the global number of street children is unknown, and that it fluctuates depending on socio-economic, political and cultural conditions, and increasing inequalities and urbanisation patterns. Union Minister of Women and Child Development, Smriti Irani, shared in March 2022 that Karnataka has the third highest number of street children in the country according to data collected by the government.