Official data shows a decline in dowry harassment cases in the city last year. Activists disagree.

Cases of dowry harassment have decreased by 22.71 percent from 2019 to 2020 in Bengaluru. Women’s rights activists attribute this to the under-reporting of cases rather than an actual decline.

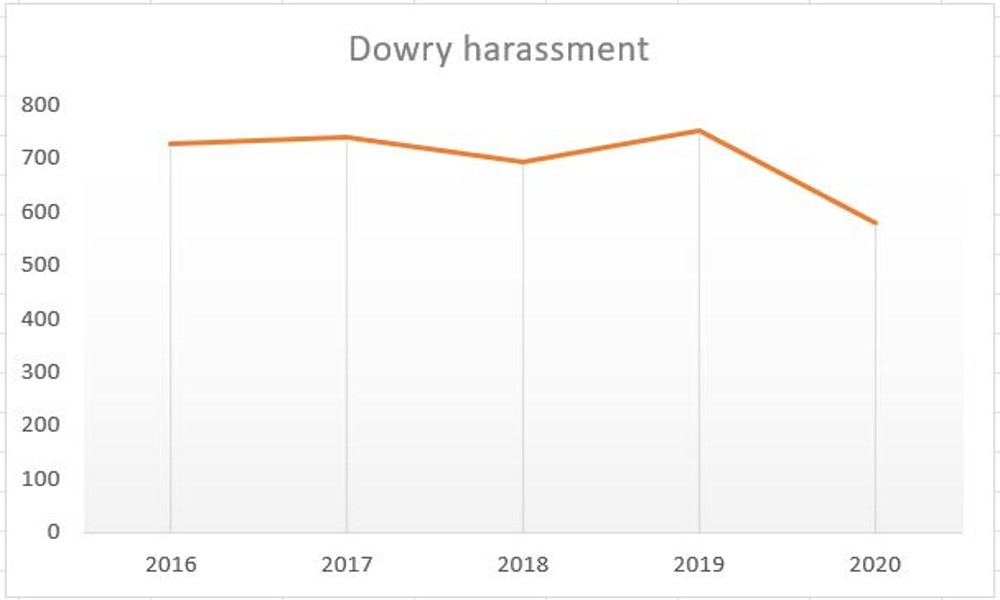

In the last five years, according to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data, dowry harassment cases have been above 690 in the city. In 2019, there were 751 cases. In 2020, the number of cases fell to 580.

Mamatha, founder of the Gamatha Mahila Sangha said that she gets three to four cases every day even now. “Cases have definitely increased during the pandemic. Unlike normal times, women were constantly in the company of their abusers. It was very difficult to report anything,” she said.

“Many of these cases which were filed went under domestic abuse instead of dowry harassment,” she added. “For most of my clients, the abuse started with demands for money, because the pandemic brought a lot of financial strain. Men would ask their wives to bring money from their parents. Legally, this counts as a dowry demand, but the police file it under abuse,” she said.

Disha (name changed), a teacher, got married to a civil engineer in November 2019. The groom’s family made no demands, except that the bride’s family fund the wedding. However, when the pandemic hit, her husband ran into financial trouble. “His family used to blame me for their problems. My husband wanted my parents to buy him a car, pay off his home loan, even buy jewelery for his sister’s wedding. My family couldn’t afford that,” she said.

Disha’s case has been filed under domestic violence as the husband hadn’t asked for anything during the wedding. “The police said the money demands were simply an effect of his financial trouble. It was still dowry though,” she said.

Section 498A of the IPC deals with cruelty towards a woman by her husband or his relatives. It is closely linked with the Dowry Act, as demands for dowry after the marriage are often accompanied by violence. Reports said domestic violence cases went up to around 25 a day from 10 in the first lockdown in Bangalore.

The Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961—and its subsequent amendments—are aimed at preventing the giving or receiving of dowry. It applies to all religions. The minimum imprisonment is five years and the minimum fine is either Rs 15,000 or the amount of the dowry. This act applies to money or property given at, before, or any time after the wedding.

The police said the reason for the decrease in cases was mainly the pandemic. “It is difficult to discern whether a situation is a dowry case or not. We do file complaints in case of domestic violence. In either case, we follow the Supreme Court’s guidelines before filing any family-related dispute,” said Kumar, the head constable at the Women’s Police Station, Banashankari.

In a 2013 order, the Supreme Court said that all matrimonial disputes—including those under section 498A—were to first be settled by mediation centres rather than filing an FIR. While this is possible only if both parties consent, this is often the reason police refuse to file complaints, said Mamatha. “A dowry harassment case is first referred to a Santhvana Centre. They go through a weeks-long process of mediation, extract some promises from the husband, and end the matter. By the time the abuse starts again, the woman is too disillusioned with the process to go through it again,” she said. She added that most of the police are not sensitized to deal with gender issues; they prefer such “domestic” cases to be settled within the family.

“The police station sends the husband and wife to us. We talk to them, try to mediate the dispute for a few sessions. In cases where no compromise can be reached, the police file an FIR under the relevant sections,” said Nilima, from the Parihara Counselling Centre in Malleshwaram.

For most women, the process is a punishment in itself. Jyoti, a 35-year-old, was abused by her husband within a week of their marriage with dowry demands. When she tried to reach out to police stations, they kept delaying her case, telling her to bring more papers and reports every time. Eventually, the financial strain got too much for her family, and they agreed to a settlement. She divorced her husband and got back the dowry amount. “There were bruises all over my body and these people still wanted papers. He still remains unpunished for all the pain he inflicted on me,” she said.

Studies showed that the pandemic caused an increase in domestic abuse mainly because of unemployment and shortage of police force. This increase was also predicted in a report by the World Health Organisation in April 2020. It states that being cut off from the support of friends and family in the lockdowns would be a major factor in this increase.

“In India however, family is often the reason many women stay in abusive situations,” said K.S. Vimala, convener of the Akhila Bharatiya Janavadi Mahila Sangathane. “Indian ‘values’ like staying with your husband and his family—no matter what—are what prevent so many women from speaking out. It is also the reason our legal system has such a backward attitude—because we prioritize the family and not the women who are suffering,” she said.

Yogita Bhayana, a women’s rights activist, said that crimes against women are always grossly under-reported. “So many women are not even aware of their rights. The process needs to be simplified so that they get justice,” she said.

Dowry and domestic violence in Bangalore-Karnataka are well drafted in the report.

Not only in this state but overall,alongwith the legal support providing education and financial independence to women can change this scenario …