IISc researchers have discovered why anti-TB drugs fail against the deadly bacteria, paving the way for scientists to develop more effective drugs in the future.

Bengaluru: Scientists in Bangalore have found what makes the TB bacterium tick.

A team of researchers at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), led by Prof. P. Ajitkumar at the Department of Microbiology and Cell Biology, published a research paper in Frontiers in Microbiology in December 2020, where they discovered why common anti- tuberculosis (TB) drugs like Rifampicin are not completely effective.

This discovery has helped identification of molecules, which the bacterium uses to build an armour-like capsule around itself to survive in the continued presence of lethal doses of Rifampicin. This discovery explained how the TB bacterium protects itself from getting eliminated by Rifampicin.

“The armour-like capsule is drug-resistant,” said Dr Subhasish Mahapatra, a doctor at Calcutta Medical College. “Its physical appearance is undefined which helps the bacteria to not get identified by the drugs, and get killed.”

He said that every drug has a mechanism of action, which means the effect that the drug causes in the body. Rifampicin’s mechanism of action works on a normal bacterium. But if the bacterium modifies itself, Rifampicin would stop being effective.

“Rifampicin has to be given in the case of normal tuberculosis. In some cases, we do a test to know if the bacterium is resistant to Rifampicin or not,” said Dr Mahapatra. If it is, then Rifampicin would not work. The doctors then call it a case of multidrug or extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis treatment under Rifampicin takes around six to12 months. But Rifampicin is generally considered to be a narrow therapeutic index drug. The doses have to be very carefully maintained. If not or if Rifampicin is given to a patient having heart or liver failure, their condition would worsen.

Rifampicin also has a lot of side effects —ranging from itching and dizziness to diarrhoea and heartburn. Dr Mahapatra said that it’s still in use because it is the only drug that somewhat counters TB bacteria.

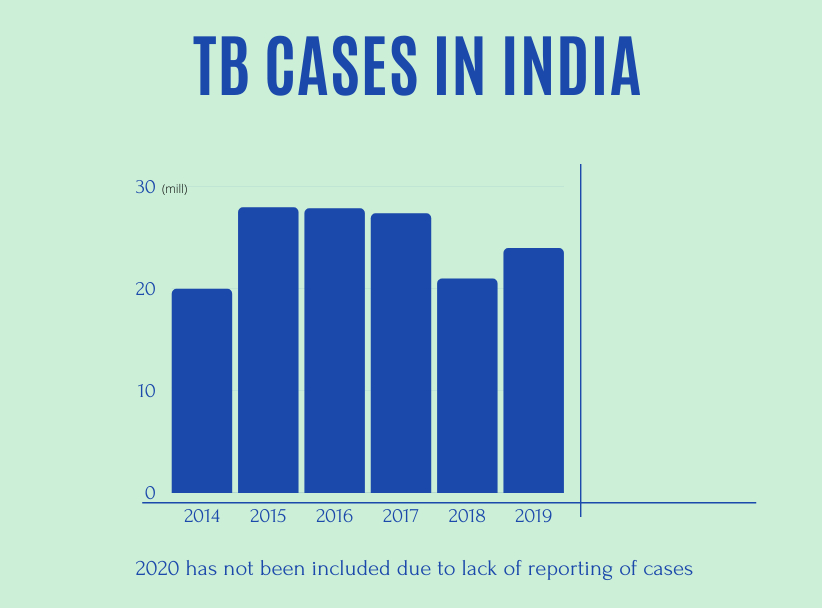

This article mentioned that because of the pandemic, the health ministry found a reduction of 25 per cent in Tuberculosis in 2020. But on further inspection, the cause for this has been determined to be the lack of detection of cases due to the pandemic.

India reported 2.4 million cases of TB in 2019 with Karnataka having around 91,000 cases. Tuberculosis is still a major cause of concern for Indian citizens.

What makes the TB bacterium unique?

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a highly adaptive bacterium. It can survive in the environment for several weeks. When TB patients spit sputum (spit) on the road, it falls there, gets dried up and the dried particles get carried by the wind. If anybody inhales it, that person shall get infected with tuberculosis.

Dr P Ajitkumar, the lead scientist in this research, said that people living in congested areas have a higher chance of contracting the bacterium. Normally the infection spreads through coughing. When a TB patient coughs, the aerosol (a suspension of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in the air) comes out and stays in the air. When one inhales it, the bacterium gets into their system and the person becomes infected.

What is unique about this bacterium is that it can survive outside for many weeks under any climate. Once it goes inside the body, it can evade the macrophage. Macrophages almost act like police in our body. Theyare responsible for inspecting, detecting and destroying anything they deem as “foreign”. This bacterium will then be swallowed by the macrophages and forms what is called a phagosome. The bacterium will then be inside the phagosome. Now the phagosome should fuse with the lysosome, which has a lot of degradative enzymes that will kill the bacterium.

But this bacterium works differently. Once it is inside the phagosome, it will produce one particular molecule which will quote the surface of the phagosome with an armour-like shell. “Then this phagosome cannot fuse with the lysosome and so the bacterium remains protected. The bacterium will then come out at a time when it finds the conditions suitable.. How it recognises it, that no one knows, it’s a big mystery,” said Dr P Ajitkumar.

It can also stay in low oxygen conditions called a granuloma. Even if you dump lethal doses of the drug, it won’t kill the bacteria in the granuloma region. The armour restricts the drug from being effective. If a person dies and is buried, the bacterium continues to survive.

The chances of a person getting infected with tuberculosis for the second time isn’t as unlikely as one might think. “20 to30 per cent of people who have been cured of TB get TB again. It doesn’t have to be through a fresh new infection,” said Dr P Ajitkumar.

“If someone after getting cured, takes a drug that suppresses the immune system, like the steroid drug, the bacteria will sense that the immune system is weak. It is still unclear as to how they do it. But once they sense it, they will come out, grow, and divide in the body and the person will get tuberculosis again,” he added.

Dr Kishore Jakkala, who did his PhD under Dr P Ajitkumar, had published a paper on how hypoxic (low levels of oxygen) mycobacterium tuberculosis also develops a thick layer to prevent itself from getting killed by antibiotics.

“We wanted to know what are the morphological changes happening within the bacteria and how it is helping mycrobacteria to survive within its macrophage. Most antibiotics aren’t effective on such mycrobacteria and it takes as long as six months to treat TB. So we wanted to know what could be the reason behind this,” said Dr Jakkala.

The case of a TB patient

While conducting his research, Dr P Ajitkumar met a lot of people who had contracted the TB bacterium. Among the people he met, was a driver who was harbouring a TB bacterium that was resistant to multiple anti-TB drugs.

TB treatment regimen has four frontline antibiotics. According to the lead scientist, most people visit the doctor when they find blood in their spit which happens at an advanced stage. They undergo treatment and within ten days they find their spit blood-less and stop their treatment.

Since he (the driver) was the sole earner of his family, he couldn’t undergo the entire treatment. He said that the drug made his body very weak and he could not go to work.

“When the treatment is stopped midway, the bacterium continues to survive inside the body and senses that the drug concentration in the body has reduced. Then the bacterium mutates itself randomly and becomes resistant to the antibiotic. So when the person goes back for treatment, the doctor has to prescribe a different antibiotic since the former one would not work anymore,” said Dr P Ajitkumar.

Elimination of TB by 2025

India plans to eliminate TB by 2025. This research done by IISc identifies the very problem behind the ineffectiveness of common anti-TB drugs. The research team said thatnew and more effective drugs can be made now. They have identified the additional molecules that form the armour-like layer. If a drug can be made that can target those molecules, the layer would not form and the bacteria would die. The lead scientist believes it will take at least another decade for this drug to develop.

But Dr P Ajitkumar doesn’t believe drugs are the solution to cure TB. “As long as poverty exists in the world, TB shall exist. We need more awareness about tuberculosis. We need to tell people that it is a curable disease if they go through the entire treatment regimen.”

He said that we need a TB vaccine that gives lifelong protection. The BCG vaccine that we took in our childhood doesn’t provide lifelong immunity. “Drugs won’t help in the fight to eliminate TB. If we develop a vaccine providing immunity for life, TB shall get cured,” added Dr P Ajitkumar.

This research was published in Frontiers Media journal. In 2015, this journal came under controversy when it was added to Beall’s list of potential predatory journals. After that, it faced severe backlash from the scientific community. This Nature article then criticises the journal’s inclusion in Beall’s list and talks about the flaws of Beall’s list.