A weaver is paid a maximum Rs. 300 for each saree that he weaves; the market price of the same saree starts from Rs.8000.

It is around ten-thirty in the morning. He has already worked for three straight hours. On his left is a bag of overflowing kandagis (sticks threads are woven around in), on his right, a plastic bottle of water, and before him, the shiny, blue wavy saree he is gradually weaving out using the handloom.

He is Subhash, a weaver from Hireupnal village, one of the rare places in India where weaving sarees by hand has not been entirely killed by modern solutions. Situated about 465 kilometers from Bengaluru, the capital of the southern state of Karnataka, Hireupnal is in Ilkal district, the district which has lent his name to the world famous Ilkal sarees.

A legacy that dates back 600 AD, Ilkal sarees are a staple wear of the women of North Karnataka. Over time, the saree type has seen experimentations with several design palettes and fabrics (both in cotton and silk). For years, dyers and weavers have imparted their creative wisdom into beautifying them, enhancing them.

However, since the past 10 to 20 years, this traditionally handwoven saree is facing a crisis, writhing under the inevitable effects of modernization; and the brunt of this is being borne by many traditional weavers in the villages of Ilkal. Most of them say weaving is the occupation they are best skilled in, and they would not shift to powerlooms, as shifting would mean producing inferior quality sarees, which would “both diminish their craftsmanship and betray the craft itself”.

Subhash, who is more often than not the first one to wake up and start work in Hireupnal, has been a weaver for over 40 years now. He said the number of handlooms and handloom weavers in Ilkal has drastically reduced. While he cited several reasons for such an outcome, the most significant one has been the low income from hand weaving, he said.

Subhash said he earns anywhere between Rs. 200 to Rs. 250 for each saree he weaves. For him, an experienced weaver, a saree typically takes around two days to be handwoven, when worked on for six to seven hours a day. “Even if I am able to weave one whole saree every day, I can only earn a little more than Rs. 6,000 in a month which is not enough to run my family,” he said. He added that both his sons work as electricians and his daughter is married. “My children do not want to or know how to weave. They say neither is weaving a respectable job, nor does it fetch enough money. Unfortunately, I agree with them.”

DP Chourey, another weaver who works with Subhash under the same shed explained that most weavers in Ilkal work under seths, or the owners of handloom machines who also provide raw materials to weavers. The seths own saree businesses and outlets where the finished sarees are sold. Pointing at the saree he was weaving, Chourey said, “For this saree, Seth will pay me Rs. 250 only, but will sell this in the market for a minimum Rs. 6,000.” The selling price for hand woven Ilkal sarees ranges between Rs. 8,000 to more than Rs. 15,000, staff at saree retail outlets in Ilkal said.

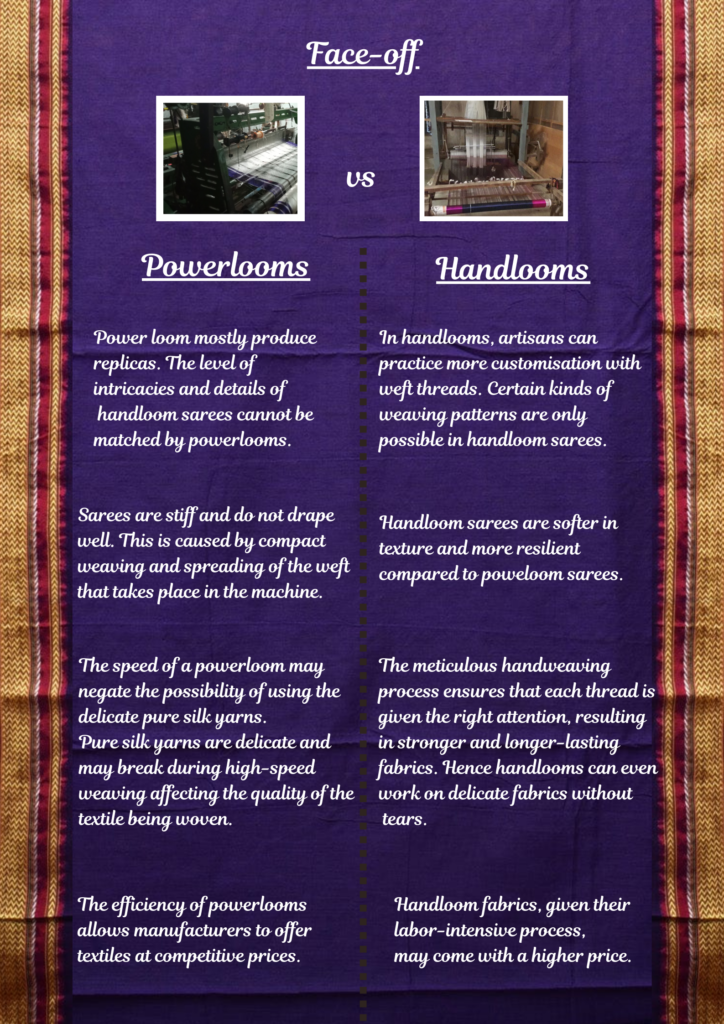

He also explained that the key difference between a handloom and a powerloom lies in how the weft is set. In a handloom, the weft yarn, rolled inside a handmade shuttle, is thrown in the loom by hand, a step which needs some amount of dexterity and hence, only experienced weavers can achieve. Whereas, in a powerloom, this process is accomplished using specialized machines. This also differentiates the texture of powerloom sarees (smooth and stiff) from handlooms (uneven and soft), he added.

Bhagya Sapparad, owner of around fifteen handlooms, producer and distributor, (for whom Shubash and Chourey work) said she cannot increase the wages of her weavers at present because even her business is running at a loss. Firstly, while demand for raw materials and hence price has increased, demand for the finished product has reduced or remained constant, she added.

Secondly, she said the lack of enough cotton processing plants in Karnataka increases the cost of production of the sarees significantly. Cotton is abundantly grown in Karnataka’s black soil, but the produce has to be sent to Maharashtra and back for processing to cotton threads. These are two major reasons which have raised the cost of production of sarees by Rs. 100 or Rs. 150 per unit, she explained.

The Karnataka Handloom Development Corporation (KHDC) was established under the Karnataka Government’s Department of Handlooms and Textiles in 1975 to provide support to weavers. According to their official website, the corporation helps weavers by providing raw materials at subsidized rates, offering training and production-based incentives, facilitating government schemes and enabling easy marketing and distribution.

This story, in a podcast.

However, starved of funds, Ilkal’s KHDC has witnessed massive decline in its membership of weavers, an official from the corporation said. Back in 2005 or 2006, KHDC, Ilkal had around 20,000 handloom weavers registered under it, a number which has now reduced to around 2,000 to 3,000, he added. He explained that the main reason behind this has been reduced funding to the corporation which has led to meager income being paid to the weavers (around Rs.150 to Rs. 200 for each saree). The lack of funding at times also causes inconsistency in providing raw materials or good quality raw materials to the weavers during which they are left unemployed, he said.

“We used to receive around Rs. 3 crore in 2015 or 2016, the funding kept reducing until last year (2023), when we received only Rs. 90 lakhs,” he said. The salaries of some 40 employees working at the Ilkal KHDC have to be disbursed from this fund itself, further reducing the amount meant for artisans’ development, he added.

Further, the production-based incentive, where, if a weaver produces more than the average, their items are bought at a 10 to 15 percent higher price, has not been renewed for the past three years, due to the fund crunch, he also said.

Shashank, a weaver who formerly worked at the KHDC Ilkal unit said most weavers often worked overtime to get in on the incentive, but when it was stopped,a large number of them gave up working overtime or quit altogether, further reducing the overall productivity of handlooms.

The corporation’s Managing Officer Ramachandrappa said he has sent proposals to the state government to increase the funding, but has not received replies to any.

The KHDC official further noted that the total number of handlooms in Ilkal has drastically reduced to just 5,000 or 6,000; whereas five to seven years ago, the number was 30,000 to 40,000. About 70 percent of weavers have switched to powerlooms, he reasoned. “And why wouldn’t they?” he asked, “Powerlooms can produce up to three to four sarees per day, plus, the chance for mistakes is much limited there.” He added that for each saree, if a weaver earns Rs. 150, s/he will be able to earn 13,500 rupees a month, much higher than what s/he can earn from handlooms.

The Indian weaving industry has, over the years, seen a mass exodus of weavers from handlooms to powerlooms, according to an article published in the Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, titled Power-loom weaving in northern Karnataka: Problems and Prospects. The total number of handloom weavers and allied workers in India, corresponding to the “Fourth All India Handloom Census” (2019-20) was 35,00,512, whereas the powerloom sector provided employment to more than 44.86 lakh people in India, according to a 2013 survey by the Ministry of textiles. Several research papers note that the number of artisans employed in powerlooms has only gone up since then.

At around one p.m., Subhash and some other weavers eat lunch. K Dharmendra Kendhuli, a retired weaver who is also a small businessman selling handloom Ilkal sarees in the local market, often visits them.

Kendhuli connected the unlikeliness of a chance of revival of the handloom sector to the diminishing interest of the youth in the craft. He said that many who could have continued with the family craft have left the villages for search of better, respectable jobs in the cities.

He explained the weaving of sarees by hand, (which also involves some footwork) demands quite a lot of time and patience, which the younger generation lacks. “I have two sons, both help me in the business, but none of them are interested in weaving.”

Janardhan Dharmendra Kendhuli, the younger son, who sells sarees in and around Ilkal on his scooter, is well known in Hireupnal. “I could never sit for more than two hours working at a handloom, I got bored. I chose to work as a dyer instead, and now, I also help my father in marketing his business,” he said.

His nephew, Akash, is a class seven student. He said he wants to be a professional gamer when he is enough grown up. He added that he has no interest in weaving. “I do not want to be termed as a bunkar (weaver) when I grow up, it is seen as an ignoble profession,” he said.

Another major reason for the declining curve of Ilkal’s handlooms is the lucrative employment opportunities youth find in Ilkal’s profitable red granite industry, a rock whose mines are widespread in Ilkal and surrounding areas. A clerk from Pandurang Hoti Chamundeshwara Weavers’ Society in Kushtagi said the granite industry is increasingly employing people of all age and gender. The internal and export demand for red granite has been rising; hence the industry can provide good wages to its labourers, he explained.

However, in such a situation, hope rests with weaver families like the Sakas. The Saka family is one of the very few full weavers’ families remaining, where every member is a weaver. Their home, in the Nekar Colony of Hire Otageri, around three kilometers from Hireupnal, is a beautiful two level house, with the lower level being a mud lain room dedicated to weaving, with handloom machines, manual and electric charkhas installed.

Malappa Saka, the head of the family said that everyone in his family- wife, three children and himself, are weavers. Chandrashekhar Saka, his younger son, who is in his second year of undergraduation, pursuing a Bachelor of Arts degree, is one of the few young people who is interested in and are practicing handloom weaving, Malappa said.

Chandrashekhar said he owes this trait to his grandfather and father Malappa, who had taught him weaving when he was a child. He added that although he is engaged in other jobs, he always takes time out for weaving. “Fondness for the craft has been ingrained into me from a young age, and that is what gives me the willingness to keep pursuing it,” he explained.

Bhagya Saka, the eldest sibling, is a teacher in a government school. But that has never prevented her from continuing with weaving, Malappa said. “It is like when you want to read a book after a long day at work. The cackling of the handloom is what soothes me and helps me unwind after I come back from school,” Bhagya said.

Yalamma Saka, 82-year-old aunt of Malappa, lives two houses down the street. She said she has been a weaver for as long as she can remember. “When I was younger, this (nekar) colony would have so many handlooms working at all times, that you almost couldn’t hear the person sitting next to you. But now, there’s silence most of the times. It makes me very sad,” she said. However, she added that she is glad all her grandchildren are amateur weavers.

The government of India conferred the lkal Saree with the Geographical Indication (GI) tag in 2007. The GI sign is used on products to confer to them a specific geographical origin and they hence possess qualities or a reputation that are due to that origin.

The KHDC official said most weavers are not even aware of the GI tag. “The GI tag is meant to retain the authenticity of the sarees, which should ultimately benefit the weavers, but has that been ensured by the government?” he asked. The GI tag benefits the seths who sell it in the market at a higher price, owing to its supposed uniqueness, but the monetary benefits of the increased selling price do not necessarily reach the weavers, he explained. “Has it been guaranteed that the increased overall profits will reach the weavers?” he questioned.

Laila Tyabji, founding member and chairperson of Dastkar, an NGO for crafts and craftspeople said, “The structure of decentralised production is such that marketing or trading remains outside the weaver’s domain and s/he is restricted to the task of weaving. In this scenario, it seems unlikely that GI-related benefits might trickle down to the weaver,” she said.

The GOI has had several provisions aimed at uplifting the handloom industry through a series of national textile policies (1956, 1981, 1985, 2000). However, as an article from The Wire notes, despite the government’s mandate to protect and encourage the handloom sector, covert policies and bureaucratic measures fully backed the exponential growth of powerlooms. The scheme of Conversion of Handloom to Powerlooms, a policy document passed 1954, legitimized the powerloom sector in government policy and its growth was ensured.

Around 10 co-operative societies work for the cause of handloom weavers in Ilkal, Kendhuli said. They are responsible for training weavers in accordance with changing fashion trends, providing raw materials to them at subsidized prices and facilitating government loans and schemes, he explained.

Ashok Chandrappa Sachi, chairman of Ilkal Weavers’ cooperative producers’ society Ltd., said their society works to ensure that government schemes such as the Nekar Samman Yojana, Weaver Mudra scheme, and schemes covering life and health insurance is availed by weavers. “But I am certain not all weavers are beneficiaries of the schemes,” he said. He however, could not furnish with details of how many weavers are so.

He further said that the government aid dedicated to reviving and enhancing this sector, gets lost, misused or embezzled in the hands of corrupt members of a few co-operative societies, through whom the government sends money.

Several weavers registered under the Seva Sindhu portal (which is a mandatory requisite for availing the Nekar Samman Scheme) said they are yet to receive money for 2022 and 2023. They also said that when they did receive it, Rs. 5000 was a meager amount yearly; even before that the amount given was only Rs. 2000. They also said that the scheme requires many documents which all weavers do not have: Aadhar card, ration card, proof of residence, income details, active bank account details etc.

Abdullah, a weaver, said that he could not register himself under the scheme because by the time he collected all the documents required, the window to apply for the scheme had expired.

The Handloom Reservation Act was implemented to provide for reservation of certain articles for exclusive production by handlooms. However, the reservations have been repeatedly violated by the powerloom sector, which has flooded markets with powerloom imitations sold as handloom fabric.

In a survey and research article, “Can handloom regain its lost glory?” published by the National Institute of Science, Communication and Policy Research, the authors find that awareness about government schemes and reach of benefits is very low among handloom workers.

This multi-pronged plight of handloom weavers is not restricted to Ilkal however. Kanchipuram of Tamil Nadu, Sambalpuri of Odisha, Banarasi of Uttar Pradesh, Bandhani of Gujarat and Tant of West Bengal are also in the same deep waters, a 2023 research article published in Emerging issues in Business, Economics and Accounting book reveals.

Laila Tyabji, from Dastkar, said the potential of Indian crafts in the world market is immense. Tyabji said she believes that innovation does not mean abandoning tradition. She therefore emphasized the need to recreate traditional processes (such as hand weaving) in novel and fascinating ways. She further said that the awareness about handwoven fabrics among customers is low. “Very few can differentiate handloom sarees from powerlooms, and due to increased purchasing power in today’s times, they don’t necessarily care that handloom sarees will last

longer than powerlooms’,” she said.

She added that one of the main hindrances to the spurt of handlooms is greedy middlemen. They should be eliminated, and handloom weavers should be empowered to buy and sell their raw materials and products themselves, she said. “Weavers should also be imparted good quality training to compete with the productivity of powerlooms. The youth should be rewarded with incentives to increase their encouragement and engagement with the sector,” she explained.

The ‘Textile and Garment Policy 2019-24’ has been envisioned to provide a stimulus to the textile industry and generate five lakh new employment in five years in the state. It also aims to attract investments worth 10,000 crore rupees.

But weavers like Subhash are unaware of all this. He said his only wish is to maintain the decent standard of life he is living now through weaving, as no other profession comes to him as easily. At around 4:30 p.m., he wrapped up his day’s work. On the way back home he told his friend Chourey, “I think the blue saree would look even better with a white border.”