Exposure to pesticides has resulted in more than 120 cases of organophosphate (OP) poisoning among farmers every month during the crop season. Water scarcity, a declared drought, and failed crops worsen the problem. Amidst this, the urgency for awareness of farmer welfare schemes, and access to adequate healthcare remains.

In the sweltering heat of May, Hanumanthappa trudged wearily to his home after a long day of dousing his rice crop with herbicide. Sitting in front of a table fan in a dim cottage room, he ate a piece of mysore pak to regain some energy. He began to feel giddy and weak. Trembling, he walked to the bathroom, to spray cold water on his face, but soon, he collapsed, only to regain consciousness the next day. The doctor told him that he had suffered an acute case of organophosphate (OP) poisoning.

Surrounded by agricultural fields, 91 kms from Raichur district, is Sindhanur village, among the many in Karnataka where farmers continue to suffer from pesticide poisoning. The 52-year-old farmer, Hanumanthappa, lacked sufficient knowledge regarding the proper usage of pesticides and their detrimental effects on human health. After inadvertently consuming sugar contaminated with Butachlor pesticide, he lost consciousness.

In Sindhanur’s Taluk Genral Hospital, around 2000 cases of OP poisoning are registered every year.

Somanagowda, 38, one of the paddy farmers affected by pesticide poisoning in Turvihal village, laments that his body does not have strength as it did before. “I experienced breathlessness, followed by fits and seizures. As my body trembled and grew cold, my cousins tied me to a cot with a rope and sari, unable to keep me still. They carried me to the nearby Primary Health Centre (PHC), from there I was taken to the Taluk General Hospital,” he recalled.

He had sprayed an insecticide named Carbaryl, based on seller’s assurance that a single application of Carbaryl would safeguard his crops for the next three months.

“The doctors said that the pesticide penetrated his body through the skin. Due to the lack of improvement of his health, I borrowed Rs. 1 lakh from people to admit him to a private hospital in Ballari. We still need to repay Rs. 40,000,” his wife Sudhanya said.

She also said that her husband’s loss of appetite, along with persistent dizziness, headaches, and body pain, remained unresolved by doctors. “Our monthly medical expenses are Rs. 2,000. Due to financial hardships, our two children were forced to drop out of school.”

According to the data by Karnataka State Agriculture Department (KSDA), there are 2296 marginal farmers, 2024 small farmers, and 2549 large farmers in Sindhanur.

These farmers handle dangerous chemicals directly, while consumers unknowingly ingest high levels of pesticide residues present in various foods. Data from Ramaiah Advanced Testing Lab, Bangalore, shows that residues of over 25 toxic pesticides, including DDT, monocrotophos, and phorate, exceed the maximum allowed limits in the produce people consume daily.

According to farmers, many pesticides like Butachlor and Carbaryl are still being sold illegally, despite being banned by the Indian government.

Medical experts say that farmers in Sindhanur frequently face heightened exposure to pesticides, particularly during the preparation and application phases in the crop seasons. Dr. Ayyana Gouda, Taluk Health Officer, Sindhanur, said “Many farmers have been exposed to significant levels of neurotoxic and carcinogenic chemicals like chlorpyrifos, dimethoate, mancozeb, and captan for extended periods, ranging from 20 to 25 years. A prevalent side effect is headaches followed by vomiting. Prolonged exposure to these toxic chemicals is linked to various neurological disorders among farmers. Moreover, the general population is also at risk due to contaminated food, consumer products, or pesticide drift from fields. Many studies show that organophosphates and carbamates are the primary chemical pesticides affecting the brain.”

Pesticides and fertilizers are commonly used in dry areas like Turvihal village in Sindhanur because they don’t receive water from the Tungabhadra Left Bank Canal (TLBC). To maximize the yields, farmers often spray pesticides three to four times when one application would do. Last year, due to low rainfall in Karnataka, the second crop (Rabi) wasn’t sown. Water supply from the TLBC stopped on November 30, 2023, and is expected to resume around July this year.

Pushpa, a 44-year-old farm laborer, has been working in fields since she was young. She lives in a rehabilitation camp (RH 1) and works there. Farm workers like Pushpa are at high risk of pesticide poisoning. “I don’t know the names, but some pesticides smell so bad that our clothes stink for weeks, even after washing them with soap,” Pushpa explained. “Since we touch the sprayed soil directly, our skin burns, we get rashes and boils, and often feel sick. When we complain, the farm owner tells us to leave.” Pushpa, a mother of three, and her husband both work as daily wage earners. She earns Rs. 250 for a 12-hour workday, while her husband earns Rs. 540 for the same hours.

Representatives from NGOs say that the farmers do not think of pesticides as poison; they see it as a part of their routine activity.

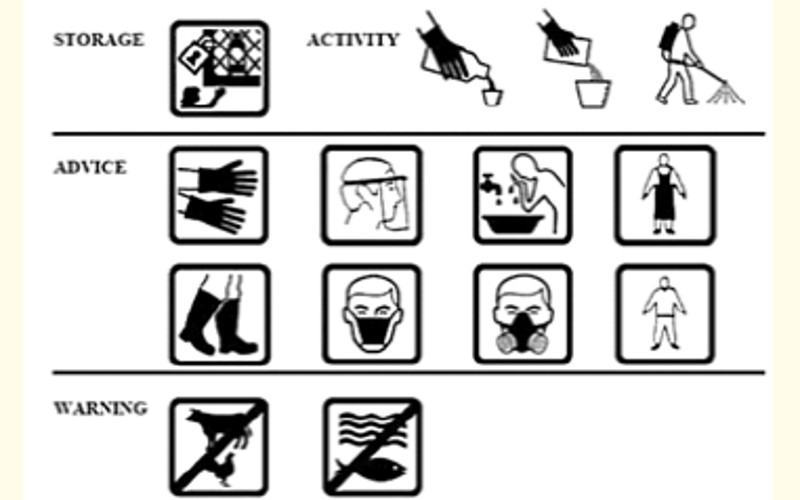

B.G. Deshpande, Secretary of Kisan Bharathi Trust, said, “Many people suffer from pesticide poisoning while spraying crops because protective clothing is either too expensive, unavailable, or unsuitable for hot and humid climate. In Sindhanur, less than two per cent of farmers wear protective gear such as mask and protective glasses, when using pesticides. Safety instructions are often provided in English, and not understood due to various reasons, including lack of education.”

Pesticide containers often use pictograms to warn farmers about the dangers of toxic chemicals, but a study in West Africa revealed that many people who handle pesticides do not understand these pictograms and it may confuse them.

High chemical residue not only impacts farmer health but also harms the environment, biodiversity, and soil health. Deshpande, who is also a poultry farmer, explained that his cattle became ill from consuming contaminated fodder. “The straw we feed our cattle is adulterated with pesticides, causing many of them to get sick and reducing the quality of their milk,” he said.

Another farmer said that healthy soil has a pH between six to eight. However, due to excessive chemical residue, the soil has become acidic, with a pH level ranging from 10 to 11.

Deshpande added, “Salt-affected soils cause significant problems like reduced crop growth, poor water quality, loss of soil life, and faster soil erosion. These soils make it harder for crops to absorb water and essential nutrients. As a result, farmers end up using more fertilizers and pesticides to compensate.”

The officials say that the farmers are reluctant to adopt organic farming and use less pesticides due to the competitive mindset amongst the community for more yield. Arun Desai, the tehsildar of Sindhanur taluk, said, “In Sindhanur, organic farming is mainly associated with the upper-middle class, but this cannot be generalized. Majority of the farmers, particularly those working on leased lands, are forced to prioritize profitability due to agreements with landowners. This economic pressure often outweighs considerations for long-term soil health or environmental sustainability.”

He added, “To promote sustainable and alternative farming methods, we started the Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana and the Rashtriya Krishi Yojana, which offer input subsidies to traditional farming practitioners. However, the implementation of these schemes remains a challenge due to the existing competitive mindset among farmers. Many farmers are focused solely on surpassing yield records. This can only be achieved through heavy chemical usage.”

Agricultural experts argue that the government fails to thoroughly investigate the causes of crop failures. Deshpande said, “Soil testing is not regular here. The agriculture department should conduct tests every season, but they only do it once every six to eight years. Due to limited awareness about soil health, farmers resort to using pesticides. Additionally, the major soil testing centers are located in Raichur.”

He also mentioned that farmers aren’t interested in practicing organic farming because it demands more time and resources. “I’m not growing this rice for myself, someone else is using it. Why should I bother?– That’s the mindset of every farmer here,” Deshpande explained.

Farmers say that switching to organic farming would require at least five to 10 years to produce good organic crops. Many farmers lease land from owners who live in cities like Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Chennai. The farmers said that these owners prioritize high yields and aren’t concerned about organic farming. They expect a minimum yield of 50 bags of rice. On the other hand, practicing organic farming would fetch them around 20 to 25 bags of rice.

Also, the farmers said that the completely leveled land limits their options for trying different types of farming or growing other crops.

Rejection in the global market

Excessive use of pesticides is not just harming farmers’ health, and jeopardizing their livelihoods; it is also causing international markets to reject Sindhanur’s rice.

Rice produced in Sindhanur faces significant rejection in the global market due to high pesticide residue. According to the data by All India Rice Exporters Association (AIREA), 35.64 metric tonnes of rice was exported from Karnataka last year. The value-wise exports were about Rs. 42 crore. According to AIREA, roughly 80 per cent of the total exports were rejected at the port due to high pesticide content.

Many exporters complained about the rejection of the consignments on an almost daily basis, because of the pesticide residues found above permissible limits in the processed grain.

The Sona Masoori rice in Sindhanur is first sent to Tamil Nadu ports from the local rice mills. From there, it is exported to countries like the US, Myanmar, Malaysia, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh.

A rice exporter from Tamil Nadu (requested anonymity) said, “Around 10 to 12 containers, each carrying 15 metric tonnes of Sona Masoori and Basmati rice were returned by several countries last year. In March, 2023, seven containers were returned by Myanmar, and Singapore too returned our containers on the basis of high residue of pesticides against the required limit.”

“Earlier the restrictions were imposed by European Union (EU) only but now it is spreading across all the countries which import Sona Masoori rice,” he added. High dependence on pesticide stems from the need for better yields, water scarcity, and a lack of government support for alternative crops.

Farmers say that they remain unaware of the consequences of high pesticide residues due to a lack of initiative from both the Agriculture Department and the State government to raise awareness. “Despite the usage of non-recommended pesticides like Acephate, Carbendazim, Thiamethoxam, and others, there hasn’t been any intervention to curb their usage. Pesticide companies, with their large network of dealers, continue to influence farmers, leading to widespread use of these harmful chemicals. Unless the government steps in, farmers are unlikely to stop their usage, and continue to be easily influenced by the persuasive tactics of these pesticide companies,” another exporter said.

To ensure that the support reaches the poorest farmers, the government has established Samparka Kendras (contact centers) at the village level, equipped with agricultural officers and soil testing facilities. Despite these efforts, awareness of sustainable farming practices and their associated health risks remains low among farmers, worsened by inadequate labeling of chemical inputs.

Nadagowda, a wealthy farmer, said, “If I start growing rice for export, my overall production might decrease. If there’s a market for rice within India, why should I focus on producing rice for export? The government needs to educate farmers about the benefits of using fewer fertilizers and pesticides. Many farmers are unaware of this and need more information.”

He added, “Organic farmers should also learn about value addition to succeed.”

Nazirama N, General Manager of Karnataka State Agriculture Department, said that putting a ban on the supply of these pesticides would prevent their usage among farmers. “Farmers often spray double dose of several pesticides, which is also responsible for high chemical residue in the crop. If a pesticide is used at the time of its requirement in a recommended dose, then its residue would not be beyond the permissible limits in the crop,” he said. “Despite not being essential for crops, farmers habitually use these pesticides,” he added.