Despite recommendations from governments and experts, many fishing boats don’t have modern navigational equipment.

A few years ago, during Durga Puja, Niranjan Das was hoping to return home as soon as possible to spend time with his family. A fisherman from Kakdwip in West Bengal, he was in a fishing boat in the Bay of Bengal. There were eighteen people in his boat, all expecting a better catch. Unknown to them, their boat had entered the territorial waters of Bangladesh. Niranjan’s boat was seized by the Bangladesh Navy in 2019. He had to stay in a Bangladeshi prison for four months.

Each year, several boats like Niranjan’s cross into Bangladesh as they are not equipped with modern technology to detect their positions.

In 2020, the Government of India unveiled the National Fisheries Policy, 2020 that required all fishing boats to be equipped with transponders or communication systems when out at sea. However, the policy is yet to be implemented on a large scale.

“The boats often lack navigational equipment,” said Pradip Chatterjee, President of DakshinbangaMatsyajibi Forum – an organization of fish workers in South Bengal. Consequently, the boats cross into the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of Bangladesh without even realizing it.

“Unlike the land borders, there are no fences made of barbed wires in the sea. The fishermen cannot detect it without modern technology,” Chatterjee added.

In 2019, at one instance, 519 Indian fishermen were detained by Bangladesh.

Once the fishermen are detained, they have to wait till a court grants their release. The process can last several months. Niranjan, himself stayed in a jail for four months. It took a toll on his family as he was the sole earning member.

Shikha Das, Niranjan’s wife, said that they were only getting Rs. 1,000 from the owner of the boats as compensation. “We have three children in our home. How can anyone survive with that little amount?” she exclaimed. Niranjan’s son, who was in school, had to drop out and start working in a small stationery store to bring home some money.

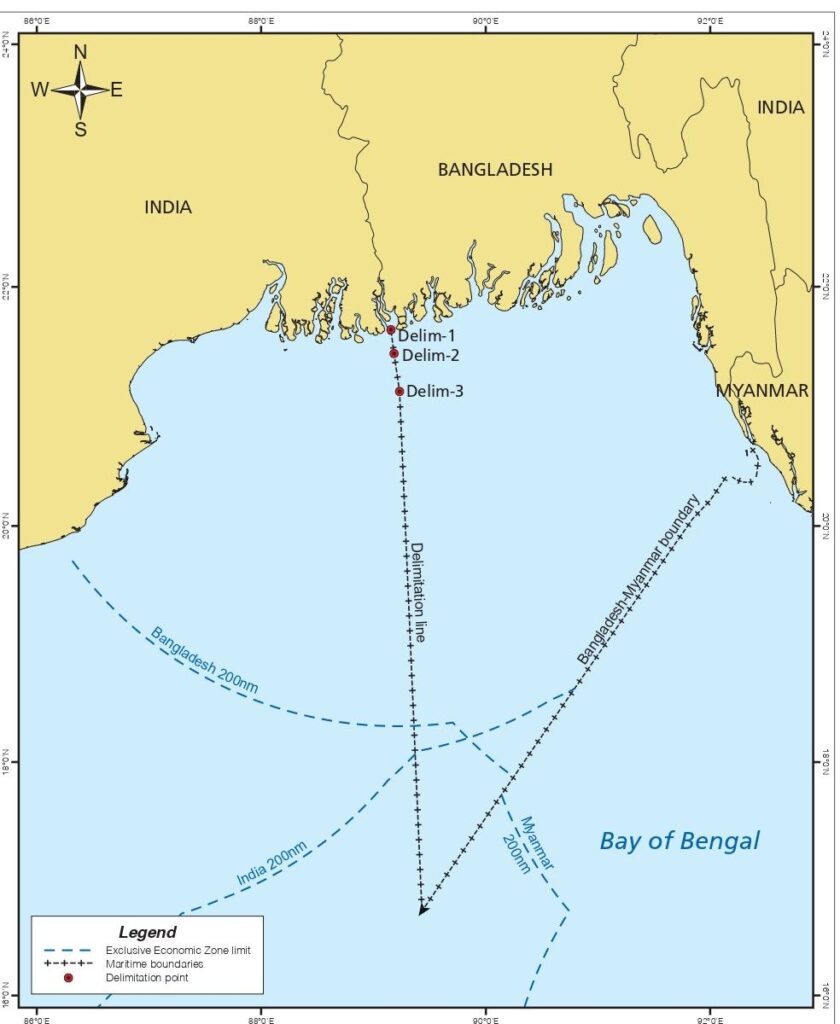

The United Nations Convention on the Law of Seas, 1982 defined an EEZ of a country as the area of the ocean where the country has exclusive rights to explore and harvest marine resources. An EEZ of a country stretches to 200 nautical miles from its coastline.

The northern coast of the Bay of Bengal spans 737 kilometers, stretched between India and Bangladesh. Since Bangladesh gained independence in 1971, both countries have made allegations of trespassing against each other due to a lack of an accepted maritime border.

In 2014, the two countries decided on the border after a ruling by the International Court of Arbitrations in Prague. It has been eight years since the judgment but not all fishermen are aware of it.

Moreover, experts feel that the issue does not get the attention it deserves. Sohini Bose, a research fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, said, “This problem is not given much attention until it attains overwhelming severity, as is seen in the India-Sri Lanka fishermen dispute.”

She added that India and Bangladesh had signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on Blue Economy promises to probe into the issue of fishermen transgression in their shared maritime space. This MoU is yet to be converted into a legally binding agreement.

However, the fishermen knowingly cross into Bangladesh on some occasions. Chatterjee added that because there is fierce competition between owners, sometimes the boats are asked to travel further into the sea to bring more harvest.

He cited the example of Hilsa – a type of Herring that travels into the rivers during the breeding season. “Even a few decades ago, the fish could be easily found in the Hooghly river. Nowadays you have to travel so much farther to catch them,” Chatterjee said.

Researchers have found several factors behind the change in the migration of Hilsa. Soumyadip Purkait, an associate professor at the West Bengal University of Animal and Fisheries Studies said that fish don’t enter into the estuaries because of siltation. It affects the depth of the river, stopping the fish from migrating.

He added that overfishing has severely depleted the fish population over the years.

The state has laws that prohibit fishing in the breeding season but the state government does not enforce them properly. “If you don’t allow the fish to grow, how would their population increase?” he explained.

The Department of Fisheries reported that approximately 4, 50,00 people in West Bengal are involved in marine fishing. The state yielded 1.82 megatonnes of fish in the 2018-19 financial year.