Bangalore’s large population is underserved by its 2,877 Anganwadi centers (AWCs), which often lack basic amenities.

Bangalore city not only has fewer anganwadi centres than it needs, but many of these centres lack basic amenities. Data from the Department of Women and Child Development’s (DWCD) Balangala portal shows that out of the 2,877 AWCs, 738 lack electricity, 545 don’t have access to drinking water, and 959 are without toilets.

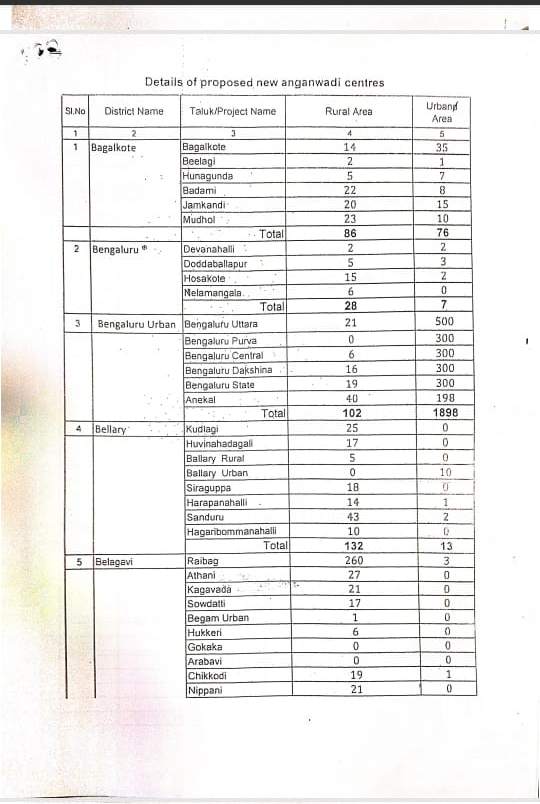

Karnataka currently has 65,911 AWCs, with 2,877 of these located in Bangalore. Among these, 457 centres are sponsored by the state, while the remaining are centrally sponsored. According to the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) guidelines, there should be one to two AWC for every 800-1000 population.

Within the confines of a room that was once a small cycle repair shop, Ramavani, an anganwadi worker, manages to pack 28 children. These children arrive at 10 am and spend six hours at this AWC in Ambedkar slum. If any of the children need to use the restroom, they must go to a street corner nearby or wait until they get home because the centre does not have a toilet.

This AWC is just one of centres in the city that lacks sanitation facilities. B Nagarathnamma, a retired anganwadi worker (AWW) said, “Students are forced to practice open defecation. We visit some neighboring houses and ask if we can use their restrooms. The low rent for this centre prevents us from securing a better place with basic facilities, so we’re expected to adapt to the situation.”

Among the 2,877 AWCs, 1,050 are owned by the DWCD, and 355 operate on BBMP lands. The remaining AWCs are run in community halls, mahila mandals, temples, school buildings, and various other locations. Officials have mentioned that the rent for AWCs on BBMP lands is Rs 8,000, per month, while it’s Rs 6,000 for urban areas and Rs 2,000 for rural areas.

Hemavathi, the state program officer for ICDS said, “In a city like Bangalore, Rs 8,000 is too low for rent. We must set up one AWC for every 1,000 people, and to find accessible land can be challenging in densely populated areas. The location also needs to be convenient for people. Unlike rural areas, where people are ready to donate land, it’s challenging in urban areas to acquire land. We are willing to establish AWCs if the BBMP provides us with land, but generally, they have their own plans for the available sites.”

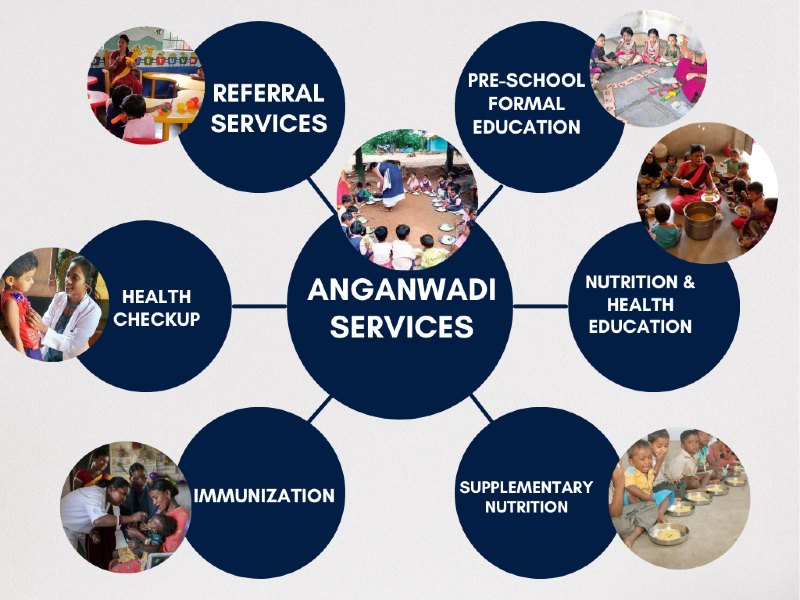

Anganwadis play a key role in providing early childhood care and nutrition to support the holistic development of children. Due to a growing population and urbanization, the demand for new AWCs has risen, leading to migration and the emergence of urban slums.

Dr. B Usha, Joint Director of ICDS, said that in this year’s Empowered Programme Committee (EPC) meeting, she pointed out the lower release of funds for anganwadi services in the previous year. “We identified 4,244 AWCs in non-ICDS areas of the state and requested the Ministry of WCD for funds, but we are still awaiting feedback and are reviewing the guidelines,” she said. For Karnataka and other southern states, the meeting was held in Kochi on August 2, 2023.

Officials said they have ‘strictly’ instructed the Child Development Project Officers (CDPOs) to relocate rented buildings lacking basic amenities to schools. So far, they have moved 100 AWCs to schools.

“We submitted an affidavit to the High Court stating that all AWCs must have toilet and drinking water facilities. This affidavit is reviewed monthly by the committee led by Justice E.V. Venugopal. In our last meeting on October 15, we discussed infrastructure, nutrition, budget, and health. By December, we aim to relocate a minimum of 500 AWCs lacking basic amenities to schools,” Dr. B Usha said.

A long wait for wages for AWWs in Bangalore

It is not just the centres alone that are ignored. The basic rights of anganwadi workers who work at the grassroots level are also overlooked.

They face poor working conditions like delayed salary payments, lack of incentives for enrolling beneficiaries in certain programs, and the additional workload of working in schools, attending health checkups, and conducting surveys.

Nagarathnamma, assistant director of the Karnataka State Anganwadi Workers’ Union said, “We’ve been working in the centers for a long time, and suddenly the CDPO decides to fire us. Our salaries are often paid late. Even though we should get paid on the 7th of each month, it often comes much later, sometimes after two or three months.”

Many AWWs have not received the additional incentives granted to them for enrolling beneficiaries in specific schemes. Furthermore, they also lack financial security.

Nagarathnamma added, “We haven’t received any financial aid from the Gruha Lakshmi scheme, and it seems like the DWCD is indifferent to our situation. The government collected a large amount from us through the New Pension Scheme (NPS) Lite, but the distribution of those funds by our CDPOs was unequal.”

Asha Jyoti, an AWW from Kolar said, “In Bangalore and many other taluks, we were not provided with the Rs 200 incentive for enrolling women in the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY) scheme.”

Asha also spoke about the problem of inadequate infrastructure, and how it’s unsuitable for pregnant women. Under the Matru Purna program, pregnant or feeding mothers come to AWCs to get a meal. “Before this scheme, they used to collect food grains from the center and cook at home, which was effective. However, in Karnataka, more than 50 percent of AWCs lack adequate space. They operate in small rooms, outdoors under trees, or on the streets. Pregnant or feeding mothers struggle to find a proper place to sit and lack the necessary infrastructure for meals. As a result, 90 percent of the food allocated for Matru Purna has been misused,” she said.

Experts say that the challenges to child survival and well-being are rooted to flawed policies, poor project design, lack of appropriate Monitoring and Evaluation (M and E), and governance issues. Mr Allen Ugargol, public policy professor at Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Bangalore said, “The multifaceted nature of malnutrition needs to be considered in the execution of ICDS. While a child’s nutritional well-being depends upon various factors beyond food intake, it remains a crucial element that attracts families to engage with the program. Additionally, supplementary feeding should be strategically used as an incentive for underprivileged and malnourished children and their mothers to engage with health and nutrition education initiatives.

In order to reach India’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), it is essential to take comprehensive action on all the aspects. “Merely increasing the number of anganwadi centers won’t effectively address child malnutrition. To achieve the MDGs, a significant policy change and improved implementation are important. Without these changes, the attainment of the MDGs is highly unlikely,” Mr Ugargol said.