Experts say that the absence of specialised doctors in public healthcare facilities not only impacts people’s health but also affects them financially.

With his grandchild’s hand firmly grasped in one hand and her medical documents in the other, the 66-year-old man stood by, awaiting an auto to return back to his village. It was a sunny day at Manvi, the relentless sun beat down, the little girl’s face glistened with sweat. He gently pulled her to the shaded place under a billboard that stood nearby.

Anumappa was on his way back from a private hospital in Manvi town, where his grandchild was receiving treatment for her broken arm. Unavailability of specialist doctors at the government hospital made him choose a private hospital for treatment of his grandchild. There is no orthopaedic specialist present at the taluk hospital, and the existing doctors are not always available, he complained.

This was not the first time that Anumappa had to depend on private hospitals for medical treatment. Two years ago, he was diagnosed with Tuberculosis (TB) and incurred around Rs. 2 lakh in medical expenses at a private hospital in Raichur.

Anumappa had a severe cough and was feeling unwell for a couple of days, initially he sought treatment at Manvi Taluk General Hospital. Despite receiving medications, his condition showed no improvement. After waiting for a week, he was taken to a private hospital in Raichur by one of his daughters. It took his daughters and son-in-law over two years to repay the funds they borrowed from various sources for his treatment.

Anumappa voiced the concern of many in the Taluk who had no way other than to depend on private hospitals for treatment, which often cost them more than what they could afford.

The healthcare delivery system in Manvi faces significant gaps in providing quality healthcare services to the people. The taluk grapples with insufficient medical infrastructure and shortage of specialised doctors at the Taluk Hospital.

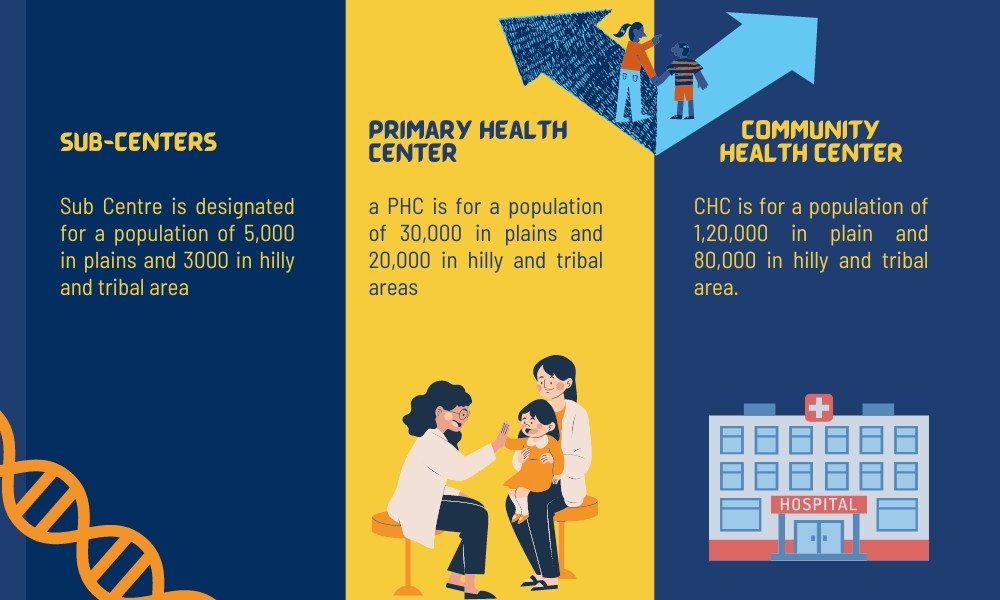

The public healthcare system in India comprises different tiers with increasing specialisation and population size served from primary to tertiary. This includes Sub Centres (SCs), Primary Health Centres (PHCs), Community Health Centres (CHCs), Sub Divisional/ District Hospitals (SDH), District Hospital (DH).

According to the Health and Family Welfare Department under Karnataka Government, Taluk hospitals are referred to as Sub Divisional/ District Hospitals for the purpose of standardisation under the revised guidelines of Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS). They form an important link between Sub Centers, PHCs and CHCs on one end and District Hospitals on the other. They act as Referral Units for the Tehsil/Taluk/Block population in which they are geographically located.

The IPHS guidelines requires Sub-District hospitals to offer essential services such as General Medicine, General Surgery, Obstetrics & Gynecology, Pediatrics, Orthopedics, Anesthesiology, Ophthalmology, Dentistry, ENT (Ear, Nose, and Throat), Psychiatry, and Radiology. Additionally, desirable services include those provided by Dermatologists, Cardiologists, Nephrologists, Urologists, and Gastroenterologists.

However, Taluk General Hospital in Manvi only has four specialist doctors—an ophthalmologist, a dentist, a surgeon, and an anaesthetist. They manage all the patients coming to the hospital, said Rajesh R, Block Programme Manager of the Taluk Hospital.

Doctors in the hospital have raised concern over their increased workload. Dr. Aravind, anaesthetist and Chief Medical Officer of the hospital said, “The hospital doesn’t have enough specialist doctors, the existing doctors handle all the cases that come to the hospital from Medical Legal Cases (MLCs) to accidents, assaults, police cases, and orthopaedic issues.” Padmavathi, a Nursing Officer at the general hospital, said, “Since there are not enough doctors in the hospital, the existing doctors treat the patients in shifts, even though many of those cases may not be their specialty.”

Adding to the workload of the existing doctors, the hospital does not have a general physician, noted Dr. Aravind. It becomes hectic for us to attend to patients seeking specialist treatment as well as those from the general Outpatient Department (OPD), said Dr. Deepa, dentist at the hospital.

Patients also complain about the unavailability of doctors during hospital hours. Fathima, a 33-year-old housewife who came to the hospital from Ballatagi, which is almost 17 kilometres away from Manvi, had to wait till four in the evening to meet the doctor. She said that she couldn’t meet the doctor in the morning, as the hospital was too crowded. “The doctors left for lunch at 1 pm, according to a nurse they were supposed to be back by 3 pm. But it was already 3.30 pm, and I was still waiting there at the hospital bench,” she complained in frustration.

Padmavathi mentioned that the official service time after lunch is supposed to be from 1.45 pm to 5 pm, however, the doctors are available in the hospital from 10 am to 1 pm and 3 pm to 5 pm post lunch.

The lack of specialised doctors in the taluk hospital has also resulted in many patients being referred to the district hospital. According to the hospital record 52 cases were referred to Raichur Institute of Medical Sciences (RIMS), till February 2024. In 2023, 387 cases were referred, while the same was 245 in 2022.

Dr. Bhaskar K, Medical Superintendent, at RIMS, agreed that they receive many referral cases from Manvi. He further said that the hospital is well equipped to manage the extra load of patients from the taluk.

Dr. Surendrababu, District Health and Family Welfare Officer, Raichur, said that actions are being taken towards the appointment of doctors in the Taluk.

Experts say that the absence of specialised doctors in public healthcare facilities not only impacts people’s health but also affects them financially. Unavailability of specialised doctors in public healthcare facilities, would lead people to depend on quacks and other unscientific traditional treatment methods, affecting their health in the long run, mentioned Gowthamghosh B., Assistant Professor at the Institute of Health Management Research (IIHMR), Bangalore. He further highlighted the additional financial burden that people have to carry while seeking treatment from private facilities.

The issue of shortage of doctors is not limited to Manvi taluk, according to a study conducted by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), in August 2023, there is a reported shortage of 16,500 medical professionals in Karnataka.

The report further reveals a shortage of health care personnel, including 723 MBBS doctors, 7,492 nurses, 1,517 lab technicians, 1,517 pharmacists, 1,752 attendants, and 3,253 Group D workers. Furthermore, the report mentions that rural areas often lack enough primary, secondary, and tertiary health centres, in contrast to urban areas.

Similarly, Rural Health Statistics report 2022, published by Ministry of Health and Family Welfare points out that there is a shortfall of specialist doctors, including surgeons (83.2%), obstetricians and gynaecologists (74.2%), physicians (79.1%) and paediatricians (81.6%) in the country.

A 2023 study revealed a significant imbalance in the distribution of doctors in the public healthcare system of the country. Only 31 percent of doctors serve in rural areas where disease burdens are higher, while urban areas have four times the number of doctors compared to rural areas.

Needs more health Infrastructure

Gynecologists needed urgently

In the initial months of 2022, Manvi taluk received a separate Maternity and Child Hospital (MCH). After that, all pregnancy and paediatrics-related cases were moved to this hospital, said Mr. Rajesh.

However, the hospital is in dire need of a gynaecologist. The hospital that carries out over 100 deliveries every month does not have a gynaecologist. The post of gynaecologist has been vacant for almost one and a half years, said Dr. Shenappa, hospital’s Head and the only paediatrician. “Considering the footfall, the hospital should have at least three gynaecologists, anaesthetists, and paediatricians each,” he suggested.

Nurses in the hospital have raised concern over the challenges of conducting deliveries, especially high-risk pregnancies, in the absence of a gynaecologist. Shilpa, Nursing Officer at the MCH, said that they face challenges due to the absence of a gynaecologist while conducting deliveries, especially the high-risk pregnancies. Such cases are often referred to the district hospital, she said. “We cannot conduct C-sections in the absence of a gynaecologist, hence those cases are also referred to RIMS,” she added.

According to hospital data, out of the 1,130 deliveries conducted between January 2023 and January 2024, 499 cases were referred to the district hospital. The majority of these referrals (458 cases) were antenatal, while the remaining 41 were postnatal.

Dr. Shenappa raised concern regarding the taluk’s infant mortality rates, contrasting them with relatively low maternal mortality rates. Hospital data reveals six documented cases of infant mortality. He observed that some in the taluk still prefer home births. “Unfortunately, some families delay seeking medical attention until the eleventh hour, opting for home births. They only come to the hospital when things get complicated, in such cases getting the child out becomes more difficult,” he said.

Gowthamghosh maintains that availability of a gynaecologist could prevent 70 to 74 percent of complications during delivery. A specialist can identify complications in pregnancy at the earliest stage and take necessary measures, he said.

The National Family Health Survey 5 (NFHS-5) report states that 97 percent of births in Karnataka were institutional, and among them 64.8 percent were in a public facility.

Gowthamghosh noted that C-section requires trained gynaecologist, surgeon, anaesthetist and nursing officers. He pointed out a substantial increase in C-section rates, as indicated by NFHS-5, with over 30 percent of deliveries in Karnataka being C-sections, compared to 23.6 percent in NFHS-4. He emphasised that this surge accentuates the need for more trained healthcare professionals and increased expenditure.

Dr. Surendrababu revealed, “While a permanent gynaecologist was previously stationed at the MCH, they’ve been on unauthorised leave for two years. Despite numerous attempts to contact and resolve the matter, the situation persists, and we’ve forwarded it to the state level.” He further noted that the department has tried several times to appoint doctors in Manvi, but many doctors were found to be unwilling to work in areas like Manvi.

The way forward

Experts suggest improving infrastructural facilities in the hospital and solving connectivity issues to bring in more doctors to rural areas.

Prof. Gowthamghosh points out that doctors may take into account various factors such as geographical location, connectivity, availability of basic infrastructure, and amenities like educational institutions when making decisions about practising in a specific location. Hence, he recommends investigating the underlying reasons behind why doctors prefer not to work in a specific area and then finding solutions to it.

Attack from locals is another reason observed by Prof. Gowthamghosh behind the reluctance of doctors to work in rural areas. Dr. Aravind said that many doctors refused to work in Manvi fearing attack from locals. He shared an incident when tensions escalated between locals and doctors in the hospital, that sparked rumours among healthcare personnels on the working conditions in the taluk. Similarly, Dr. Surendrababu said that his wife, also a doctor, was not willing to work in the taluk due to fear of attack. Gowthamghosh suggest ensuring safety of doctors while working in such areas.

Dr. Rajeshwari BS, Assistant Professor at Institute of Health Management Research, Bangalore said that the government should focus on ensuring basic facilities in rural areas to bring in more doctors.

Gowthamghosh suggested improvement of medical infrastructure and connectivity in rural areas to attract doctors. He observed that many PHCs in rural areas lack basic facilities like electricity. Similarly, many operation theatres in CHCs and taluk hospitals lack medical equipment and staff. He puts forward rational deployment of doctors and other medical professionals to ensure that no areas are left unattended.

Many states have implemented compulsory service programmes to ensure availability of doctors in rural areas. However, a study conducted by National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC) on the existing regulatory mechanisms to address the shortage of doctors in rural, remote and underserved areas across five Indian states, including Karnataka mentioned that the compulsory rural service for under- and postgraduate doctors implemented in the state was grappling with weak implementation and inadequate monitoring. According to the study there is a severe shortage of medical officers and specialists especially in the northern districts of Karnataka, and compulsory rural service has been ineffective in addressing this shortage.

Gowthamghosh suggested enforcing a uniform system of compulsory service across the country. He recommended consulting with all stakeholders, especially doctors, involved while taking a decision regarding its implementation.

In October 2023, the state government eased the mandatory rural service requirement for medical graduates through an ordinance. Doctors will now be hired based on position availability or whenever there is a shortage of medical staff. In a news report, Minister of Law and Parliamentary Affairs HK Patil said that the new approach aims to optimize the deployment of healthcare professionals and avoid wastage of skilled personnel.

Representing the concern of many in the taluk, Anumappa eagerly looks forward to the day when he can trust the public healthcare delivery system rather than spending lakhs on private hospitals.