Out of the 48 BBMP night shelters, only three are meant for women. Even those go unoccupied while homeless women sleep on the street.

In the scorching heat of Bengaluru, Rangamma, a 79-year-old woman from Andhra Pradesh, is in front of a fast-food stall, seeking food. Abandoned by her two sons, she now resorts to begging near KR Market and wanders the neighborhood’s streets. No one has informed her about the night shelters provided by BBMP. She said, “My legs are weak, and my eyesight is poor, but I have to beg during the day to fill my stomach and sleep wherever I can find a spot in the market.”

Rangamma is not alone; there are many others like her who have been abandoned by their families and must beg and sleep on the streets without knowing about these shelters.

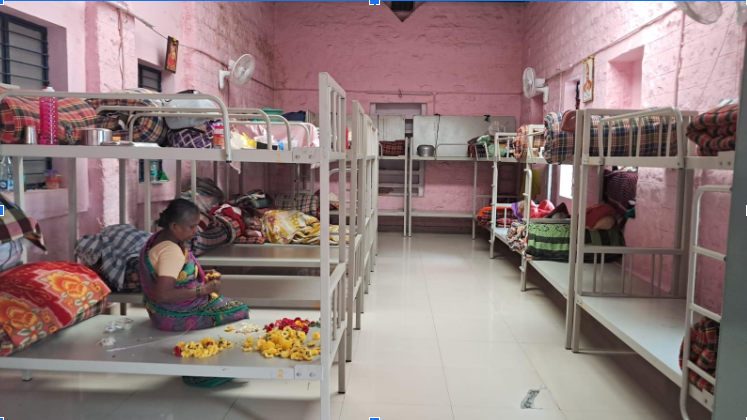

The Bruhat Bengaluru MahanagaraPalike (BBMP) operates 48 shelters in Bengaluru as part of the Deena Dayal Anthyodaya Yojana – National Urban Livelihood Mission (DAY-NULM). Janardhana Achar, BBMP Community Organizer (Welfare), says that these shelters can accommodate 1,477 people. However, out of these 48 shelters, only three are specifically designed for women; two of these shelters are in the South zone, and one is in RR Nagara. But all of them see limited occupancy. And, they are in a state of disrepair.

Each of these shelters can accommodate less than 50 people, which doesn’t align with the government’s guidelines recommending accommodation for 50 to 70 people. In the East zone, one shelter in Kumbaragundi has a capacity of 34 with 29 people staying, while another in Wilson Garden has a capacity of 22 with 14 occupants. The shelter in Yeshwantpur has a capacity for 20 people but is currently hosting 13.

According to the guidelines, the shelters should provide personal space, sanitation, medical help, recreation, and residential democracy. The shelters in the South zone are located in areas that are hard to navigate. None of them can accommodate 50 people, and lack space for personal storage, sanitary facilities and community kitchens.

BBMP officials justify the fewer shelter for women thus: there are fewer number of destitute women at the city’s bus stops, railway stations, and markets when compared to men. However, a visit to places like KR Market, Yeshwanthpur railway station, and Shivajinagar bus stand, show a different picture.

Many homeless women are sitting on the sidewalks during the day, trying to make a living by selling flowers, bananas and mosambi, or helping vendors in the Gujri area to sell used car parts. Among these homeless women, the older people are those abandoned by their families. The middle-aged or younger women are often those abandoned by their husbands or those who come from unstable family situations.

Revati, 30 years old, lives with her elderly mother and younger brother on the sidewalks near the flower market. During the day, the siblings do whatever work they can find. At night, they sleep on the sidewalks. “I have lived here for most of my life. There is no one to ask us, nobody bothers. But we make do with what we have,” she said. She earns Rs 200 to Rs 300 a day. Every 15 to 20 days, they use the public toilet to wash our hair and clothes. “It costs Rs 5 for regular use and Rs 7 if we need to wash our hair,” says she.

A study conducted by the BBMP found that there are around 4,246 homeless people in the city. This survey was part of the National Liveability Campaign and was carried out in coordination with the Impact India Consortium (IIC) in November 2019, covering all eight zones of the city. Edward Thomas, IIC activist, said that out of the total homeless population in the city, 3,380 are men, and 857 are women.

Ashwini, a 15-year-old girl living with her mother in Akshaya Trust said, “Three months ago, I had my period, and my mom was away at work. I found out about it from the Ajjis here, but they couldn’t give me a sanitary pad because the lady who takes care of us, Asha, wasn’t there that day. I finally got the sanitary pads the next day when I told my mom about it.”

Women are reluctant to come to the shelters. Sharad, caretaker of Akshaya Trust said, “It’s challenging to persuade them to join. When we pick up men, we can usually get at least 10 people at once. For women, it’s different; we need to take two residents from the shelter to talk to them and try to convince them. They are often hesitant and wary about coming with us.”

Many of the inmates in these shelters are older women, and only a few of them go to work. While some work in hotels, they are mostly daily-wage labourers. Kristina, 77, said, “I suffer from severe knee and back pain, and my left hand does not move due to an injury, making it difficult for me to use a squat toilet.”

BBMP officials point to a litany of woes when asked about the state of the night shelters. They point to several “technical challenges”. For one, they have limited access to land for constructing new buildings. What’s more, finding buildings for rent is a challenge, they say.

The residents are hesitant to give out the area for homeless individuals. Basavaraj, zonal officer for Yelahanka said, “The BBMP is not providing us with buildings for constructing shelters. We had plans to build two shelters for women, but we had to cancel them due to strong public opposition.”

Brahmananda, the zonal officer for Mahadevpura, said that there are irregularities in meetings with NGOs. “The Public Service Commission (PSC) is planning to approve four more shelters, one of which will be for women. However, the construction costs are high, it takes years to complete. The Managing Director of the DAY-NULM office has not yet approved the funds,” he said.

Reddy Shankar, BBMP Special Commissioner (Welfare) said, “Whenever we locate land that is available for shelters, government officials often have their own plans for it. We are now exploring the option of renting private buildings. There are also plans to construct a new shelter for women near the Cantonment Railway station.”

It is imperative to recognize the distinct challenges faced by women, especially those who have been abandoned or find themselves in precarious situations. Edward Thomas, IIC activist, emphasized the importance of a ‘multi-pronged’ approach, encompassing not only the expansion of shelter capacity but also outreach programs to make women aware of available resources. He said, “Efforts should be directed towards creating safe and welcoming environments within these shelters, with adequate hygiene, offering medical assistance, and empowering women with opportunities for self-sufficiency. Collaboration and coordination between various stakeholders, including government bodies, NGOs, and local communities, are vital for a comprehensive and sustainable solution to this complex issue.”

In a city of prosperity and progress, the heartbreaking reality of homeless women like Rangamma and Revati cannot be overlooked. The scarcity of shelters specifically designed for them, coupled with the challenges they face, underscores the urgent need for comprehensive solutions.