They say that work from Home (WFH) during the pandemic helped them quit unhealthy habits and improve their mental health.

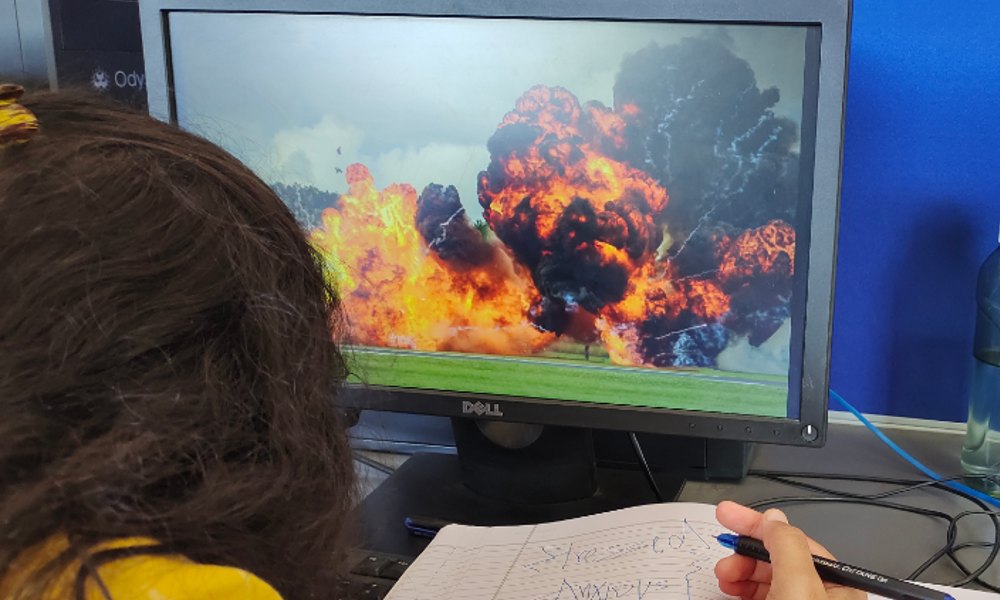

It is 6 P.M. Most of India’s corporate employees are on their way home to relax and unwind with their families. As *Soumya grabs her professional camera and purse to race down the stairs before her impatient cab driver leaves, her boss stops her and hands her files. The Bengaluru traffic plays with her anxiety as she nervously fiddles through her notes. Once home, she barely has enough time to have a sip of water — her eyes burn and her head throbs, but she powers through and meets her deadline. At 1 A.M, she falls asleep on her table. She wakes up at 7 A.M, wears her ‘PRESS’ card with pride, and sets out for another day of work.

“This is how the industry is. Although I love my job and I know that journalists don’t have a break, I wish we could just take a few days off and work from home as I did during the third wave. That helped my physical and mental health,” said Soumya.

When the first wave of Covid-19 hit India in March 2020, most companies made their employees work from home. Senior journalists say the whole Work from Home (WFH) situation was unexpected.

*Bhavya Nair, an assistant editor at a Mumbai-based media organization, said, “No one saw this coming — reporting has always been a very on-field job. Over the three waves, many people lost their jobs, and salaries got cut.” She added that the mental health of a journalist is very important to take care of. “Many journalists cannot even type a word until they have a drink or smoke in their hand,” she said.

She added that the Indian work culture is toxic. “Even when there was WFH, the lines between home and work were blurred. But the problem is also that journalists are overworked on the field. We need to stop glamorizing the whole ‘overworking’ culture,” she said.

One of the key points in the Working Journalists Act, 1955, states that a newspaper journalist cannot work more than 144 hours in a month — this excludes meal times. But over the years, many journalists who moved to broadcast and online media (multimedia) said that they must also be included under the ambit of this law. In 2017, Union Labour and Employment Minister Bandaru Dattatreya said that these journalists would be included but this has not happened yet.

“Broadcast and online media require us to constantly monitor news — there is no such thing as a holiday or proper mealtimes. That is just the way it works and to cope with it, we smoke.” said *John, a Bangalore-based multimedia journalist.

Pulmonologists said that this lifestyle could prove costly if not solved early on. Vyakarnam Nageshwar, a Telangana-based medical journalist and pulmonologist said, “That is why I think WFH is a boon. When they are at home, they can work but also take care of their habits. When our eating patterns and sleep patterns are bothered, the endocrine system which ensures smooth release of hormones, fails to do this effectively.” He added that this leads to higher stress and unhealthy coping mechanisms. “They turn to smoking and drinking and this turns into a vicious cycle,” he said.

Journalists said that WFH reduced their unhealthy habits and improved their mental health. “Although I love being back on the field, I’m worried I will slip into my old habits again. During WFH, I almost quit smoking—I meditated, turned in better quality work, and just felt happier,” said John.

Readers say they want good journalism. “Although I am not a part of the media world, I read the news regularly, as should every citizen. I feel like the mental state of someone writing an article is important so readers can get the best content. So many times, I see these sloppy grammar errors and that makes me think about what the person typing this must be thinking. Are they in a hurry? Are they stressed? As a reader, I want good articles,” said Anu, a creative writing teacher.

Media associations say that WFH proved to be a good solution for employees and the organisation. Karthik Prakash is the President of the Karnataka branch of All India Press Media Association, which essentially promotes online journalism. Karthik said that WFH is a good solution for both the journalist and the media organiation. “It increases productivity and is cost-effective. And journalists can relax and breathe so it works both ways,” he said.

*Ritu, another journalist, said that the burden of offline work took a toll on her physical and mental health. “My work is like a 24/7 shift. Everything is so irregular—my sleep, my eating, etc. I got acne and my stomach got upset. Although I love doing what I do, I really wish there was a solution for this. What if we had a time limit for WFH?” she said.

Vyakarnam added that an irregular routine affects the heart as well. “Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a condition when lung diseases block the air — this makes it difficult for the person to breathe and is fatal because the condition cannot be reversed,” he said.

Journalists also feel that they are undervalued and that this contributes to their stress, anxiety, and other mental health problems. “We are always dispensable. There is no value for us. We are overworked and our salaries are low. But we do this because we love it. We are humans too — I don’t think it is like this in America,” said *Tanya, a Bengaluru-based journalist.

American journalists say that mental health is more valued in their organisations. *Cady, a New York-based policy regulation and privacy reporter, said, “Here, reporters are more valued — we don’t have to constantly self-censor and worry about overworking ourselves to get a promotion. And I think that this takes a huge load of stress off our backs.” She added that editors and senior journalists in the US understand the importance of mental health.

“They do not see us as dispensable here. Sure, this notion is different according to the state or company, but there is a general awareness and importance given to mental health here,” she added.

Other journalists say the solution lies in taking a more grassroots approach to help journalists cope with their mental health.

Bhavya said that senior journalists and editors should empathize with young journalists’ mental health. “Journalists need to encourage each other and check- in with each other. If a junior isn’t able to cope with a particular beat, the solution may be to expose them to other beats and diversify their options. They may either float or swim — either way, they’ve learnt something. That is real journalism, and I think if Indian media can do that, it can take their mental health to a better place.”