All is not well with Karnataka’s child health scenario. The Sample Registration System (SRS) 2017 revealed that the Infant Mortality Rate in the state has gone up from 24 in 2016 to 25 in 2017.

Savyata Mishra

A few years ago, a poor couple from Hyderabad and working at a construction site in the city brought their three-year-old son for treatment at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health (IGICH). Pneumonia had caused the boy to be malnourished. After a month of close supervision by the doctors in terms of diet and medicines, the child was discharged. However, his parents didn’t come for a follow-up checkup that was advised by the doctors.

When they turned up a month later, Dr Sanjay K S, director of IGICH remembers that the child looked wan, pale and grossly underweight with skin infections running up his arms. He was readmitted to the hospital.

Although this child escaped death by a whisker, in Karnataka, not every poor child is as lucky. Reports suggest that 10,000 infants die every year in the state of diarrhea, pneumonia and malnutrition and other respiratory illnesses.

The Sample Registration System (SRS) 2017 suggested that the infant deaths rate in the state went up from 24 to 25 in 2017.

Infant Mortality Rate(IMR) is the number of deaths per 1000 live births in a given geographical region.

Reports suggest the state received Rs 1,280 crore under the centre’s National Health Mission (NHM) scheme in 2019. Only 34 percent of the funds have been utilized for improving infrastructure and staff numbers in the hospitals.

Dr Rajendra Shinda, a paediatrician, said, “Since the influx of people to this city is increasing, the infant deaths are higher than in other cities. Bangalore provides the best healthcare facilities catering to all sections of society. Sometimes, small government hospitals that have a limited number of staffs and beds face trouble managing the patients.”

Dr Sanjay, in his two decades of being a pediatrician, has seen a gradual decrease in the cases of infant mortality. He informed that in 2018-19, IGICH recorded 180-200 infant deaths. “Due to the rigorous and comprehensive nutrition and child healthcare schemes rolled out by the centre as well as the state government, infant death has been checked to a huge extent,” he said.

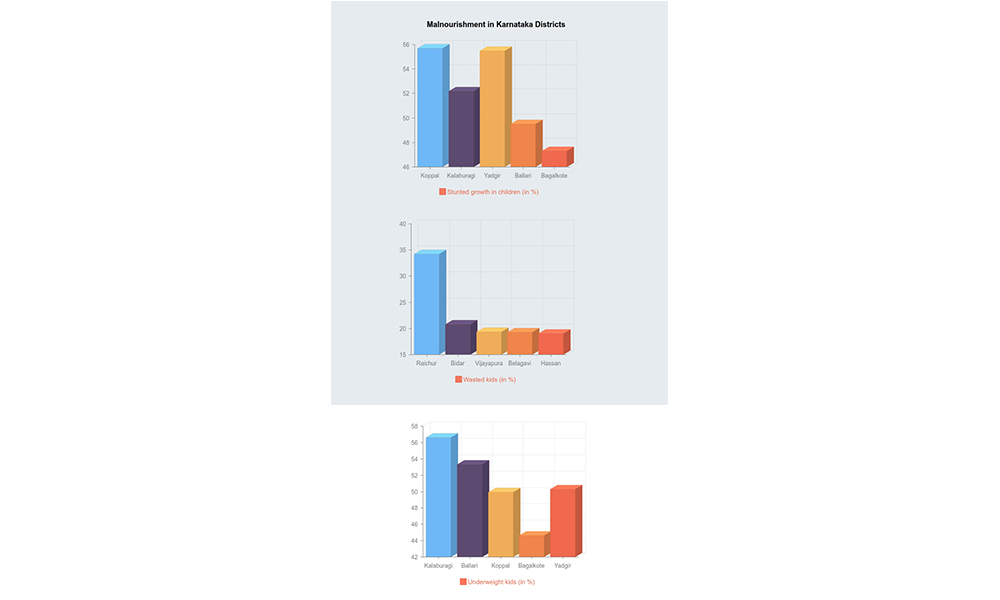

In hospitals around the city, children are being treated for malnourishment occurring as a consequence of illnesses like diarrhea, acute respiratory infections, malaria and measles, The Softcopy reported. An unequivocal response from doctors was that most of these patients belonged to districts of North Karnataka, especially Gulbarga, Dharwad, Davanagere and Raichur where malnourishment was up at 20-30 per cent.

Paediatricians feel that delayed intervention at the village and taluk level increased the morbidity rate of a simple disease, compelling parents to seek tertiary help in cities like Bangalore. In other cases, uneducated and poor parents who have migrated to a different city are extremely reluctant to give up their job to take care of the afflicted child.

A National Family Health Survey (NFHS) report states that the infant mortality rate is higher for children whose mothers have no schooling (40 per 1,000 live births) than for children whose mothers have completed 10 or more years of schooling (22 per 1,000 live births).

Dr Rajendra shared one such experience where a father who had brought his two-year-old for treatment returned to his village even though the child required medical attention. He was a daily wage labourer and couldn’t afford to stay in the city for treatment, fearing he would lose his livelihood.

Nutritional Rehabilitation Centres (NRC) are set up in various government hospitals to prevent infant death. Currently, there are 32 Nutrition Rehabilitation Centres at the district level, 21 are attached to district hospitals and 11 are attached to medical colleges.

At these centres, the caretaker of the child who has been admitted receives an amount of Rs. 259/- per day to compensate for daily wage loss. Dr Sanjay said that this initiative has proved to be an incentive for poor parents to admit their child into hospitals.

Dr Rajani, health officer at the State Department of Women and Child Welfare said, “We attempt to mitigate the child health issues from the root by providing the Anganwadi workers with training to identify ailing children and help parents in admitting them to primary hospitals. Apart from that, registers are maintained in every hospital to track and do follow-up checkups for the children who were diagnosed with diseases.”

Ms Hazira, a nutritionist and diet counsellor feels that mothers who give birth with less than two years of gap in between, usually end up in hospitals with ill and underweight children. “This is because they tend to leave the younger ones to the care of the older children who don’t know a thing about healthy diet. Negligence towards the health of the child over a long period of time results in stunted and wasted children. The aim should be to educate the families, not just individuals, to achieve nutrition sufficiency.”