Local committees are supposed to be constituted under the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013. However, many structural problems hamper the functioning of the committees.

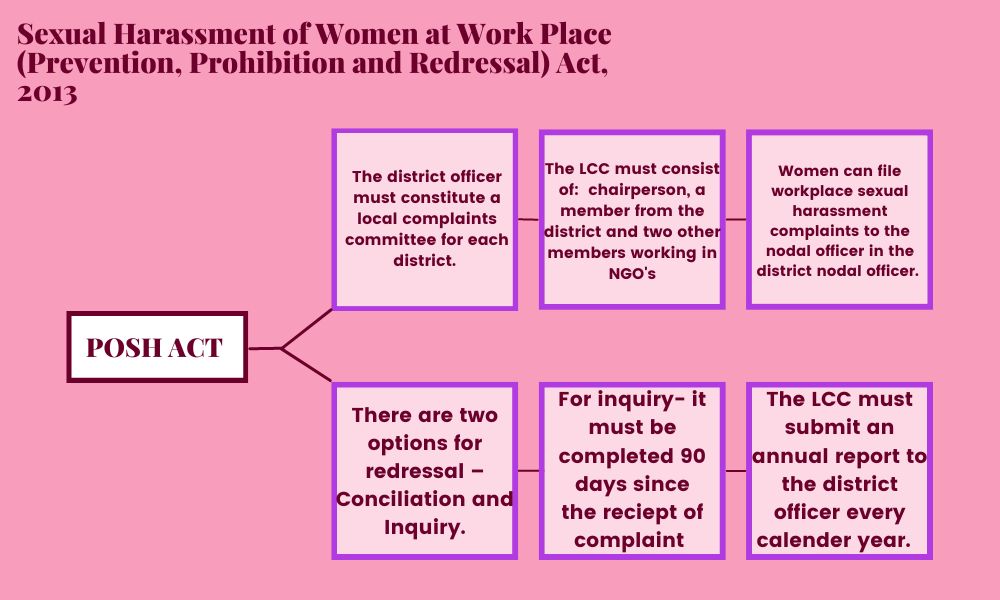

Lack of awareness about the functioning of Local Complaints Committees (LCC) is resulting in low registration of complaints. No official data is available on the constitution of committees in all 31 districts of Karnataka, as mandated by the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 (POSH Act). LCCs were formed as a mechanism for women in the unorganized sector to file complaints of workplace sexual harassment.

Veena Rai, Chairperson, Bengaluru Urban, Local Complaints Committee said, “Bengaluru is a metropolitan city so we are getting some complaints. But in rural districts even if an LCC is formed, they are not receiving any complaints due to lack of awareness.” She said that the few complaints they receive are from women employed in the IT sector and complaints from Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) working with the unorganised sector and complaints through ‘SHe-Box’. ‘SHe-Box’ is an initiative by the Ministry of Women and Child Development for filing sexual harassment complaints online.

Section 7 of the POSH Act mandates the formation of a local committee by all state governments. This is supposed to be constituted at the district level in each state. The committee has jurisdiction over the district. It must have five members, a chairperson who is a woman is the field of social work, a woman working in the particular block or district, two members working with NGOs for the cause of fighting sexual harassment.

Bhoomika, a volunteer for Durga India said that the reason for few complaints registered is because people do not know where to go or how to register a complaint with an LCC. “There is no one place where information regarding local complaints committees is given. Some are available under the labour ministry, some under the women and child development ministry. So, there is a major gap in information. There is no office where people can directly lodge their complaints,” she said.

According to Veena, this year they received only five to six complaints. Also, many of the complaints come to them via NGOs working with women in unorganised sectors. Only one or two get registered directly.

“Lack of proper funding is another reason for the poor performance of local committees,” said J. Soundararaju, a member of Bengaluru Urban, Local Complaints Committee. “The government is not paying us even the minimum charges. The court ordered the government to pay us a minimum charge of Rs.1000 per sitting. I am yet to receive Rs.28,000 for the 28 sessions I held,” he added.

Veena added that there is a lack of understanding among government departments over who should fund the committee. “In Bengaluru, from the time of establishment the committee members and chairpersons have not received their honorarium. There is confusion between the women and child department and the district commissioner’s office, as the committee is appointed by the deputy district commissioner. We are now trying to get our money from the women and child department, but still it has not worked out.” According to the POSH Act, the District Officer will be responsible for the payment.

The LCC was formed as a redressal mechanism for women in unorganised sectors and companies with less than ten people in organised sector. However, the LCC only gets complaints from women in the IT sector and educated women, its members say. “For people in the informal sector, like domestic workers, they do not know where to go to report such cases. The government is lax in implementing penalties for not forming such committees. It is more like a service offered rather than a mandate of the government,” said Bhoomika. Similarly,Veena also said that the government wakes up only when there is a major issue and takes the formation of such committees seriously.

Women in the unorganised sector are threatened if they lodge complaints of sexual harassment against their superiors. Rukmini VP, Vice President, Garment Labour Union said, “The women in the factories lodge complaints with the internal committee formed in the factory. But the committee does not function properly and they do not submit any annual reports to the government. If the women complain, their supervisors threaten and target them.”

The problems of LCC’s are not specific to Karnataka. According to a report by Economic and Political Weekly, said the LCC’s in Mumbai have not been able to conduct any awareness programs due to the “lack of monetary support from the central and the state governments that is mandated under Section 8 of the 2013 act.” This lack of awareness has contributed to the low or zero reporting of sexual abuse cases, the report said. Similarly, in the state of Tamil Nadu, the LCC of Chennai district received only one complaint between 2014 and 2019, according to a report by the Centre of Law and Policy Research. The report further said that there have been no awareness workshops conducted by the Chennai District Authority.

“After the pandemic, there have been no meetings or sessions held,” said Soundararaju.

Good and timely article on an important issue. The article correctly highlights lack of awareness in rural areas and the difficulties faced by women in filing complaints.

The point about non-functioning of committees due to non-payment of honorariums to the members of the committee is an eye opener.