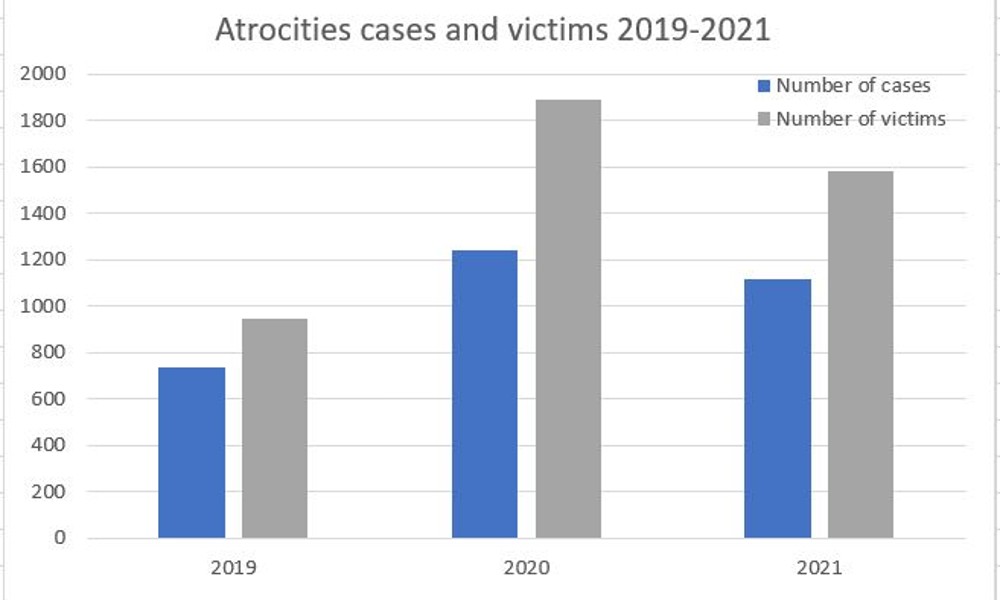

The number of crimes under the Atrocities Act has almost doubled in just one year.

The Social Welfare Department (SWD) has recorded a 99 percent increase in victims under the Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) Prevention of Atrocities Act from last year in Karnataka.

According to the SWD, there were 949 victims in 2019. In 2020, the number grew to 1889. The 2021 figures show 1580 victims so far.

Manohar Rangnathan of the Dalit Human Rights Foundation said that while one of the reasons for the increase in numbers was rising awareness, there are a lot of cases that still go unreported. “These numbers are barely scratching the surface of the problem. Most atrocity cases happen with college students, professionals like lawyers—jobs that weren’t traditionally the purview of the ‘lower’ castes. As the Dalit community grows stronger and more vocal, there are many that resent their progress,” he said.

The Atrocities Act deals with offenses like caste-based violence, discrimination and exploitation perpetrated against SC and ST people. The minimum punishment under the Act is six months and the maximum is five years with a fine.

In a recent judgment, the Karnataka High Court said that the Atrocities Act cannot be invoked in a crime merely because the victim belongs to a particular caste. Many Dalit organizations and advocates believe this order to be unfair.

Manoranjini, an advocate said that words like “intent” and “insult” add a lot of ambiguity to the Atrocities Act already. “The fact is, the caste system is a construct of the upper castes. For centuries, it has been a tool to harass and exploit marginalized communities. Any dilution in a law which protects Dalit rights tips over an already tense situation,” she said.

T.H. Savitha, an advocate in the High Court said that part of the problem is the lack of police action. “There is no effective deterrent. In the Bagalkot double murder case for example, the accused were let out on bail almost immediately. It puts the victims’ family at risk. You see many cases where the police do not act quickly, because the accused is from a prominent or powerful background,” she said.

Mallepa, a subedar in the Indian army, still remembers the day his brother and uncle were killed in the Bagalkot double murder case two years ago. “My mother got the call and we went to see the bodies. Their throats had been slit from end to end,” he said.

He added that for six months before the murder, they had been complaining to the police about the harassment they were facing. “These men were my brother’s friends. When he grew rich and started buying land in our village, they became resentful that a Dalit—someone whose family used to work for theirs—was now at par with them. They attacked our home several times. We told the police, but they took no cognizance of our problems,” he said. Crimes like these affect the whole Dalit community, as people believe it is easy to get away with the oppression, he added.

According to Shivaswami, police inspector at Uparpete Police Station, most atrocity cases fizzle out because the process is too long. He said while it is a cognizable offence and they could arrest people without a warrant, the investigation can only be carried out by a Deputy Superintendent of Police (DySP) or an Assistant Commissioner of Police (ACP). “Victims can come to the police-station with their complaints, but all we can do is file an FIR and wait for the investigation to take action,” he added.

H.R. Arunkumar, deputy director of coordination in the SWD, said the department has conducted several programs for atrocity victims. “A few years ago, we published a handbook for the police so that there would not be any mistakes in filing the atrocity cases. Recently, we came up with a contingency plan to deal with atrocity cases, including measures like periodic visits to unsafe zones and meeting people of the community,” he said.

However, Siddharaju, an activist, said the ground reality is very different from what the government plans out. “Take the employment on compassionate grounds rule for instance. It states that if a Dalit breadwinner dies in an atrocity case, someone in his family would get employment in the government. From 2017, around 201 job applications have been filed. Only 26 people got jobs. About 46 applications were rejected for reasons like filing delays,” he added.

Real reform has to come from the administration and public policy implementers, said RTI activist Narasimha Murthy. “The law has not reached the actual victims yet. For thousands of years, the Dalit community wasn’t educated enough to even recognize their oppression, much less do something about it,” he said.

It’s a fortune of reading your article regarding cast based crime. It is well-written and contained sound, with the data base. In fact this article should be considered by the respective govt deptt & social agencies for strong corrective actions. You pointed out several things in the article by collecting the factual data. I look forward to reading your next informative work. Thank you.

Sad reality of today. The information in the article is nicely put with great details.