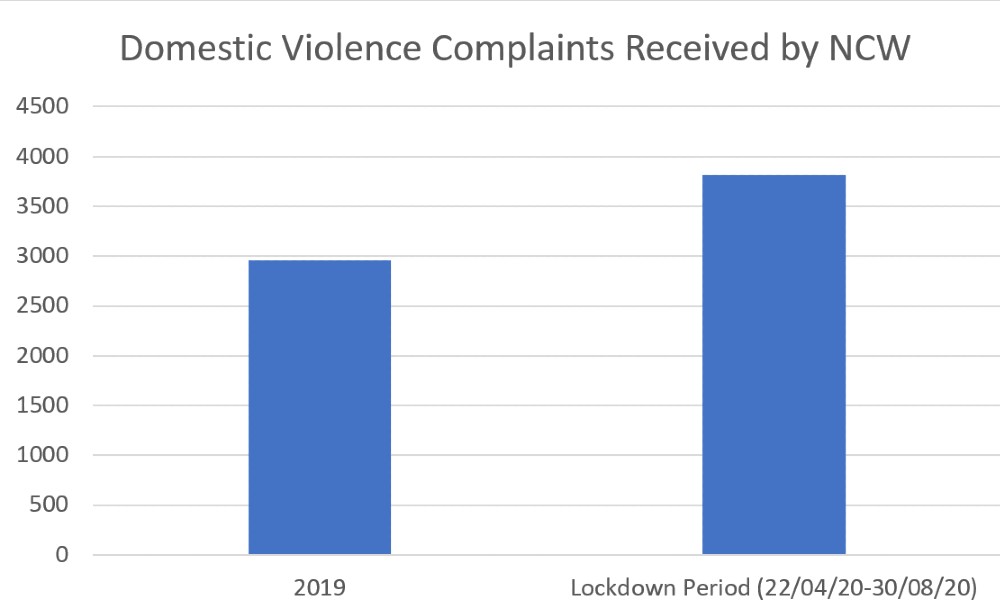

NCW received 3,814 cases of domestic violence during the lockdown. NGOs working on the ground fear that the worst might not be over yet.

New Delhi: The National Commission for Women (NCW) received 3,814 domestic violence complaints between April 22 and August 30, 2020, an RTI inquiry has revealed.

In comparison, in 2019, NCW had registered just 2,960 domestic violence cases for the entire year.

The six-month figure, believes Ananya Singh, Junior Technical Expert at NCW, is not even half of the actual figure. “During the lockdown period, all the cases were being reported through the online medium. Since the commission was shut, we couldn’t receive offline complaints,” she said.

Santosh Sharma, program leader at Nirantar Trust, who works closely with women’s collectives in Bihar, said their federations started receiving a huge number of physical and emotional harassment cases soon after the nationwide lockdown was announced.

“Before COVID-19, one federation working in four blocks would receive only one or two cases a month. During the lockdown, between April 1 and June 15, we received 380 cases of domestic violence. Even this number may not be 20-30 percent of the actual cases,” she added.

“Domestic violence is not always physical,” said Padmini Kumar, Assistant Director of Joint Women’s Programme. While working with women during the lockdown, Kumar came across increased surveillance on women’s social mobility.

“I know certain women who were asked to put the calls they make or receive on speaker, to track whom she is talking to. That is also a form of harassment,” she said.

Being a small organization, one of the biggest challenges they faced, according to Kumar, was the difficulty in keeping in touch with women and still ensuring social distancing.

“We started distributing rations in our communities and specifically asked only children and women to come and receive it. During this exchange, we would have a little conversation with the women. With our limited resources, we could only do that much.”

*Adiba Khatoon, a native of Bararhi, a small village in Rohtas, Bihar talked about the abuse she and her daughter faced during the lockdown and even continue to do, “My husband used to suspect that my daughter was talking to a man on the phone in the name of online classes. He even got her name cut from the school records. Whenever I used to intervene he used to beat me and would stop giving any allowances.”

Even after the ease in lockdown restrictions, the number of domestic violence cases in the districts Santosh Kumar works in has not returned to normalcy. The women, she said, complain of increased fights ever since the menfolk have returned home. “Earlier, they (men) used to work outside in big cities for nine to ten months and would come only twice a year on holidays. Now, the men are there constantly, which is why these cases are increasing,” she said.

“Women have started consuming less. They have stopped making any investments in their daughters’ education or health. Most of the families (in the districts she works in) have gone back at least two to three years with respect to their financial status and investments. They would at least take this much time to bounce back,” she projected.

Asks, Papia Sengupta, Assistant Professor of Political Science at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, “How inclusive can be innovation without participation? An important factor that was never taken into consideration by the policymakers was the haste in which the decision to lock down an entire country was taken. They completely forgot the angle of people, the migrant workers, the labourers, and women.”

Looking forward, she said, “Whenever we talk about policies, we must talk about who the policy is for. Is the policy for the state, or it is for the people?”

Ankita Gujar, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, St. Xaviers, Mumbai, said while most lockdowns were a sort of knee-jerk reaction, they were necessary too. She suggested that the government “should have taken quick action, and then added layers to that action as we knew more and better about the virus.”

More than this, she emphasized the need to offer better and more accessible mental health care in government hospitals along with a change in how we teach adult-learning programmes and children about violence and toxicity.

*Name changed to protect the identity of the survivor.